|

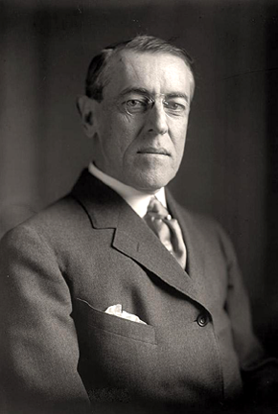

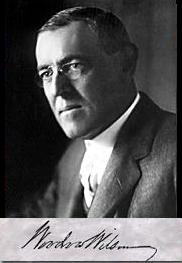

WOODROW WILSON |

|

THE 28TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1913-1921)

WILSON, (Thomas) Woodrow

(1856–1924), 28th president of the U.S. (1913–21). In domestic affairs he enacted significant reform legislation and set the course of 20th-century liberalism. In foreign affairs he led the U.S. to victory in World War I, contributing to the movement toward greater U.S. involvement in world affairs, and he played a major role in founding the League of Nations.The son of a Presbyterian minister, Wilson was born on Dec. 28, 1856, in Staunton, Va., and grew up in Georgia and South Carolina. Despite a childhood learning disability, he showed aptitude for speaking and writing. He attended Davidson College in North Carolina before going to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University), from which he graduated in 1879. Ambitious for a political career, Wilson studied law at the University of Virginia and practiced for a year in Atlanta, Ga. He married Ellen Axson (1860–1914) of Rome, Ga., in 1885. They had three daughters, the youngest of whom, Eleanor (1890–1967), married William Gibbs McAdoo, secretary of the treasury under Wilson and a Democratic party leader in the 1920s.

Academic Career.

Wilson forsook law in 1883 to study political science at Johns Hopkins University and received a Ph.D. in 1886. After teaching at Bryn Mawr College, outside of Philadelphia, and at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, he joined the Princeton faculty in 1890. His first book, Congressional Government (1885), became a classic political analysis and was followed by six other works. Chosen president of Princeton in 1902, Wilson tried to establish a preceptorial system that would provide individual instruction for students and to divide the university into colleges modeled on those at the universities of Oxford and Cambridge in England. He also deemphasized the role of Princeton’s undergraduate clubs. His forceful approach and the reforms he proposed aroused alumni opposition.

New Jersey Governorship.

After the defeats of both his college scheme and his plan for a new graduate school, Wilson became disillusioned with Princeton. When New Jersey’s Democratic party nominated him as its candidate for governor in 1910, he resigned his university post and was elected governor of New Jersey. He proved a strong, reformist governor, breaking the power of party bosses and enacting new laws to regulate elections and business activity.

Election to the Presidency.

Both Wilson’s background and his gubernatorial performance made him the early favorite for the 1912 Democratic presidential nomination. His campaign faltered, however, in the face of opposition by supporters of rival candidates, and he won at the convention only after a threatened deadlock and tough dealing by his managers, particularly McAdoo. A Republican split and the candidacy of former president Theodore Roosevelt on the third-party Progressive ticket virtually assured a Democratic victory, but Wilson campaigned vigorously, appealing for fresh reforms to curb big business and usher in what he called the New Freedom. He outpolled his opponents, Roosevelt and President William Howard Taft, although he did not win a majority of the popular vote.

Domestic Policies.

During his first term as president, Wilson, acting on his belief in strong executive leadership, pushed through major domestic programs. In 1913 and 1914 he carried out his plan for the New Freedom with the Underwood Tariff Act, which lowered duties for the first time in 40 years; the Federal Reserve Act, which set up a new system to back finance and banking; the Clayton Antitrust Act, which strengthened earlier laws limiting the power of large corporations; and the establishment of the Federal Trade Commission. In 1916 Wilson secured federal loans and marketing aid for farmers, an 8-hour day for railroad workers, and a law prohibiting child labor (later struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court). His liberalism was epitomized by his appointing to the Supreme Court the noted reform lawyer Louis D. Brandeis, the first Jewish member of that body. Wilson’s domestic record drew heavy farmer, labor, and reform votes in 1916 in his reelection over the Republican challenger, Charles Evans Hughes. He won by a narrow margin in the electoral college but had a popular majority.

Prewar Foreign Policy.

Foreign affairs demanded Wilson’s attention early in his administration, when the Mexican revolution became a civil war in 1913. Wilson’s efforts to influence it led to the U.S. occupation of Veracruz in 1914 and an expedition against the Mexican revolutionary leader Francisco (Pancho) Villa in 1916. The outbreak of World War I in August 1914 coincided with the death of Ellen Wilson, a heavy blow that was lightened when Wilson was married again in November 1915, to Edith Bolling Galt (1872–1961), a Washington widow. The warring nations vexed Wilson continually, as the British blockade interdicted trade and German submarines threatened ships and lives. The sinking of the British liner Lusitania in May 1915, killing 1198 people, including 128 Americans, created a crisis during which Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan resigned rather than risk war, while critics such as Theodore Roosevelt denounced Wilson for not being tougher. Wilson eventually convinced the Germans to moderate submarine warfare in April 1916, and tensions relaxed for a time. Meanwhile, he attempted to end the war, first through secret mediation by his confidant, Col. Edward M. House, and then at the end of 1916 with a public appeal for peace terms, and finally with his own call in January 1917 for "peace without victory." Despite Wilson’s warnings, Germany resumed submarine attacks in February. After agonizing and grasping for alternatives, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on April 2. The U.S. entered World War I on April 6, 1917.

World War I: The War Effort.

Wilson mounted the most efficient and corruption-free American war effort up to that time. A draft was instituted and functioned smoothly, inducting nearly 3 million of the 5 million men who served in the armed forces. Large numbers of American troops commanded by Gen. John J. Pershing went into combat in France during the summer of 1918, in time to join the counteroffensive that finished the war that fall. On the home front, new forms of government-directed economic organization were introduced under the War Industries Board, headed by Bernard Baruch, while several million dollars were raised through Liberty loan bond drives. The Committee on Public Information used advertising and public relations techniques to arouse popular fervor for the war effort, but espionage and sedition laws also led to widespread curtailment of civil liberties, including the imprisonment of the Socialist party leader and war critic Eugene V. Debs.

War Aims and the Peace.

Wilson diplomatically worked to liberalize Allied war aims, and in January 1918 he outlined his peace program in the 14 points, which called for national self-determination, an end to colonialism, and a League of Nations to maintain peace. The 14 points not only raised the hopes of liberals around the world but also helped shorten the war by furnishing the conditions under which Germany sued for the armistice that ended the fighting in November 1918.

At the war’s end Wilson journeyed to Europe, first for a triumphal tour of the Allied capitals and then for six months of grueling negotiations for a peace settlement in Paris. Wilson was the dominant figure of the peace conference, but he had to agree to imposing harsher terms than he would have liked on Germany in order to get the Allies to cooperate in establishing the League of Nations, which he regarded as indispensable to world peace.

Rejection of the Peace Treaty.

The worst defeat and disappointment of his life awaited Wilson when he returned home in the middle of 1919. Opposition had already gathered against the peace treaty, both from those who feared that joining the League of Nations would plunge the U.S. into future wars and from those who opposed restrictions on U.S. independence and military action. Republican senators, led by Henry Cabot Lodge of Massachusetts, threatened either to defeat the treaty by denying the two-thirds vote necessary for ratification or to attach stringent limits on participation in the league. Wilson tried to sway public opinion to his side with a cross-country speaking tour, but his health, badly strained by the war and the peace negotiations, collapsed, and he could not finish the tour. In October 1919 he suffered a severe stroke that nearly killed him and left him partially paralyzed. For three months, his wife and his doctors effectively functioned as president. Although Wilson later recovered sufficiently to perform official duties, he never regained his previous leadership, and he remained an invalid for the rest of his life. Meanwhile, in November 1919 and March 1920, the peace treaty twice failed to win Senate approval, as Wilson and his opponents both refused to compromise. The U.S. never joined the League of Nations. Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize in December 1920.

Retirement, death and personal affairs.

In March 1921, Wilson and his wife Edith retired from the White House to an elegant 1915 town house in the Embassy Row (Kalorama) section of Washington, D.C. Wilson continued going for daily drives, and attended Keith's vaudeville theatre on Saturday nights. Wilson was one of only two Presidents (Theodore Roosevelt was the first) to have served as president of the American Historical Association.

Wilson left the White House, a broken man. In the 1920 election a landslide victory was won by the conservative Republican candidate, Warren G. Harding, who called for a return to "normalcy" and a repudiation of virtually all Wilson’s domestic and foreign politics. Wilson lived almost three years longer, at one time attempting to practice law but not fit enough for any active work.

Wilson attended only two state occasions in his retirement: the ceremonies preceding the burial of the Unknown Soldier in Arlington National Cemetery, in Arlington, Virginia, on Armistice Day (November 11), 1921; and President Warren G. Harding's state funeral in the U.S. Capitol on August 8, 1923. On November 10, 1923, Wilson made a short Armistice Day radio speech from the library of his home, his last national address. The following day, Armistice Day itself, he spoke briefly from the front steps to more than 20,000 well wishers gathered outside the house.

On February 3, 1924, Wilson died in his S Street home as a result of a stroke and other heart-related problems. He was buried in Washington National Cathedral, the only president buried in Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Wilson stayed in the home another 37 years, dying there on December 28, 1961, the day she was to be the guest of honor at the opening of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge across the Potomac River near and in Washington, D.C.

Mrs. Wilson left the home and much of the contents to the National Trust for Historic Preservation to be made into a museum honoring her husband. The Woodrow Wilson House opened to the public in 1963, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964, and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Wilson wrote his one-page will on May 31, 1917, and appointed his wife Edith as his executrix. He left his daughter Margaret an annuity of $2,500 annually for as long as she remained unmarried, and left to his daughters what had been his first wife's personal property. The rest he left to Edith as a life estate with the provision that at her death, his daughters would divide the estate among themselves. In the event that Edith had a child, her children would inherit on an equal footing with his daughters. As the second Mrs. Wilson had no children from either of her marriages, he was thus providing for the child of a possible subsequent third marriage on her part.