|

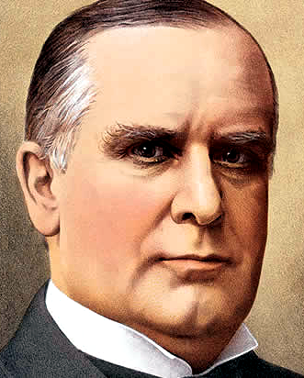

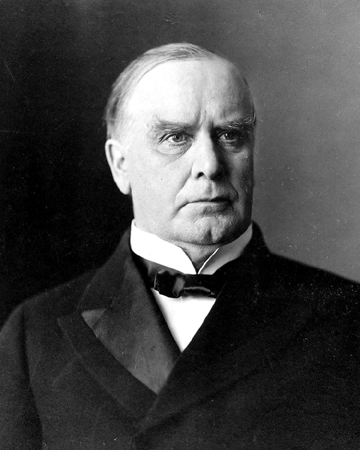

WILLIAM MCKINLEY |

|

THE 25TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1897-1901)

McKINLEY, William

(1843–1901), 25th president of the U.S. (1897–1901); his administration inaugurated a period of Republican party dominance, aided business, and made the U.S. a world power through its victory in the Spanish-American War.

Early Life.

Born on Jan. 29, 1843, to a devout Methodist family in the small town of Niles, Ohio, McKinley was the seventh of nine children of a storekeeper and iron founder. He showed himself early as a mature, serious student and attended Allegheny College for a year. At the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, McKinley enlisted and served for the duration, first as an enlisted man in the commissary department and later as an officer, after receiving a battlefield commission for bravery. For the rest of his life he was known as "Major" McKinley.

McKinley began practicing law in Canton, Ohio, in 1867 and, entering politics, won his first office as county attorney in 1869. Thereafter, his political rise was steady, with election to the U.S. House of Representatives (1877), growing influence among Republicans in his state and in Congress, and a term as governor of Ohio (1892–96). By 1896 he had become the most likely Republican presidential nominee because of his leadership in the critical state of Ohio, his long services and wide connections within the party, and his championship of economic issues, particularly the protective tariff. In addition, he had gained an able, devoted political and financial manager in Mark Hanna. In 1871 McKinley married Ida Saxton (1847–1907) of Canton, who became an invalid after the deaths of their two young daughters and took almost no part in political or social life.

Domestic Policy.

The 1896 election formed a major turning point in American politics. McKinley advocated the tariff as a way of protecting business and labor from foreign imports and defended the gold standard against his Democratic opponent William Jennings Bryan, who espoused the free coinage of silver, which would have inflated currency and aided debtors. The Republicans ran an efficient, lavishly financed campaign, and McKinley won the election by the largest popular margin since the Civil War. His administration enacted a higher tariff in 1897, committed the country to the gold standard in 1900, and generally promoted business confidence. Probably in part because of these policies, the economy recovered from a severe depression, and the Republicans became identified with economic prosperity, which made them the dominant party until the 1930s. McKinley received public vindication when he defeated Bryan again and was reelected by a still larger vote in 1900.

Foreign Policy.

Foreign affairs initially presented a troublesome distraction, as the Cuban revolution for independence from Spain created pressures on the U.S. to help free the island.

Following reports of Spanish abuse and killing of Cubans, the United States sent warships to Cuba. Spain was losing control of Cuba and had been putting Cubans into concentration camps. The United States sent ships to Cuba to try to force Spain to give up Cuba. The U.S. battleship Maine exploded in Cuban waters, killing about 260 people on board. U.S. newspapers blamed Spain for the explosion. Spain tried to avoid going to war, but pressure from U.S. newspapers, called "yellow journalism," and ordinary people, persuaded U.S. government to go to war. Some of these people just wanted Cuba to become independent, but others hoped that the United States could build a colonial empire overseas, like many European countries had done.

After resisting such sentiment for a time, McKinley decided in 1898 to intervene. The Spanish-American War had begun.

Volunteers throughout the country signed up for the war. Future president Theodore Roosevelt raised troops and became famous in leading the Rough Riders during the Battle of San Juan Hill.

A major attack occurred in the Philippines. An American fleet commanded by George Dewey destroyed the Spanish fleet. Ground battles took place in Cuba and Puerto Rico.

The U.S. defeated Spain easily in three months and they soon began to occupy and take control of these colonies after Spain surrendered. Fewer than 400 American soldiers died during fighting, but more than 4,000 Americans died from diseases such as yellow fever, typhoid, and malaria.

Spain had lost the sea war and had to give up its colonies of Cuba, the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. All of these colonies, except for Cuba, would become U.S. colonies at the end of the war. Although the war was popular, these new possessions aroused controversy, along with the recognition that the nation had become involved in world politics as a great power.

Annexation of Hawaii.

During the war, McKinley also pursued the annexation of the Republic of Hawaii. The new republic, dominated by American interests, had seized power from the royal government in 1893. He came to office as a supporter of annexation, and lobbied Congress to adopt his opinion, believing that to do nothing would invite a royalist counter-revolution or a Japanese takeover. Foreseeing difficulty in getting two-thirds of the Senate to approve a treaty of annexation, McKinley instead supported the effort of Democratic Representative Francis G. Newlands of Nevada to accomplish the result by joint resolution of both houses of Congress. The resulting Newlands Resolution passed both houses by wide margins, and McKinley signed it into law on July 8, 1898. McKinley biographer H. Wayne Morgan notes, “McKinley was the guiding spirit behind the annexation of Hawaii, showing ... a firmness in pursuing it”; the President told his Personal Secretary, George B. Cortelyou, “We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.” Wake Island, an uninhabited atoll between Hawaii and Guam, was claimed for the United States on July 12, 1898.

Disquiet also arose from the unprecedented growth of big businesses, called trusts, including the first billion-dollar corporation. McKinley showed an awareness of these concerns as his second term began, but whatever changes might have come were cut short.

Second term and assassination.

Soon after his second inauguration on March 4, 1901, William and Ida McKinley undertook a six-week tour of the nation. Traveling mostly by rail, the McKinleys were to travel through the South to the Southwest, and then up the Pacific coast and east again, to conclude with a visit on June 13, 1901 to the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York. However, the First Lady fell ill in California; causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of speeches he had planned to give urging trade reciprocity. He also postponed the visit to the fair until September, planning a month in Washington and two in Canton before the Buffalo visit.

Although McKinley enjoyed meeting the public, Cortelyou, was concerned with his security due to recent assassinations by anarchists in Europe, and twice tried to remove a public reception from the President’s rescheduled visit to the Exposition. McKinley refused, and Cortelyou arranged for additional security for the trip. On September 5, the President delivered his address at the Pan-American Exposition fairgrounds, in Buffalo, New York, before a crowd of some 50,000 people. In his final speech, McKinley urged reciprocity treaties with other nations to assure American manufacturers access to foreign markets. He intended the speech as a keynote to his plans for a second term.

One man in the crowd, Leon Czolgosz (1873–1901), a self-proclaimed anarchist, hoped to assassinate McKinley. He had managed to get close to the presidential podium, but did not fire, uncertain of hitting his target. Czolgosz, since hearing a speech by anarchist Emma Goldman in Cleveland, had decided to do something heroic (in his own mind) for the cause. He had initially decided to get near McKinley, and on September 4, he decided to assassinate him. After the failure on the 5th, Czolgosz waited the next day, Friday, September 6, 1901, at the Temple of Music on the Exposition grounds, where the President was to meet the public after his return from Niagara Falls. Czolgosz concealed his gun in a handkerchief, and, when he reached the head of the line, at 4:07 p.m., shot McKinley twice in the abdomen.

Members of the crowd captured and subdued Czolgosz. Afterward, the 4th Brigade, National Guard Signal Corps, and police intervened, beating him so severely it was initially thought he might not live to stand trial.

McKinley’s concerns, after unsuccessfully trying to convince Cortelyou that he was not seriously wounded, were to urge his aides to break the news gently to Ida, and to call off the mob that had set on Czolgosz—a request that may have saved his assassin’s life. McKinley was taken by electric ambulance to the Exposition hospital, which despite its name and the inclusion of an operating theatre generally only dealt with the minor medical issues of fairgoers. One bullet had apparently been deflected by either a bullet-proof button or an award medal on McKinley's jacket and lodged in his sleeve, only grazing the President, but the second shot pierced his stomach. Cortelyou selected Dr. Matthew D. Mann from the doctors who hastened to the scene; he had little experience in abdominal surgery or in dealing with gunshot wounds and proved unable to locate the other bullet. Although a primitive X-ray machine was being exhibited on the Exposition grounds, it was not used, and Mann carefully cleaned and closed the wound. After the operation, McKinley was taken to the Milburn House, where the First Lady had taken the news calmly.

In the days after the shooting McKinley appeared to improve. Doctors issued increasingly cheerful bulletins. Members of the Cabinet, who had rushed to Buffalo on hearing the news dispersed; Vice President Roosevelt departed on a camping trip to the Adirondacks. McKinley biographer Margaret Leech wrote,

"It is difficult to interpret the optimism with which the President’s physicians looked for his recovery. There was obviously the most serious danger that his wounds would become septic. In that case, he would almost certainly die, since drugs to control infection did not exist ... [Prominent New York City physician] Dr. McBurney was by far the worst offender in showering sanguine assurances on the correspondents. As the only big-city surgeon on the case, he was eagerly questioned and quoted, and his rosy prognostications largely contributed to the delusion of the American public."

By September 12, McKinley’s doctors were confident enough of his condition to allow him toast and coffee. He proved unable to digest the food. Unknown to the doctors, the gangrene that would kill him was growing on the walls of his stomach, slowly poisoning his blood, because the doctors forgot to drain his wound of infections before sewing the wound shut. On the morning of September 13, McKinley took a turn for the worse, becoming critically ill. Frantic word was sent to the Vice President, who was 12 miles (19 km) from the nearest telegraph station or telephone. By the evening, McKinley roused from a stupor and realized his condition: “It is useless, gentlemen. I think we ought to have prayer.” Relatives and friends gathered around the dying man’s bed as Ida McKinley sobbed over him, stating that she wanted to go with him. “We are all going, we are all going,” her husband replied. “God’s will be done, not ours.” By some accounts, those were his final words; he may also have sung part of his favorite hymn, “Nearer, My God, to Thee”. Sometime that evening, Mark Hanna approached the bedside. The senator addressed McKinley as “Mr. President”; when he received no intelligible response, he abandoned formality and cried out to his friend, “William, William, don’t you know me?”

At 2:15 a.m. on September 14, 1901, President McKinley died, the third president of the U.S. to be assassinated. Theodore Roosevelt was hastily returning to Buffalo by carriage and rail; that afternoon he took the oath of office as president in Buffalo at the house of his friend Ansley Wilcox, wearing borrowed formal clothing and pledging to carry out McKinley’s political agenda. According to Leech, McKinley's apparent recovery "was merely the resistance of his strong body to the gangrene that was creeping along the bullet's track through the stomach, the pancreas, and one kidney" Czolgosz was put on trial for murder, on September 23, 1901, in Buffalo, nine days after McKinley’s death, was found guilty, and sentenced to death, in federal court, on September 26, and was executed by electric chair, in Auburn Prison, on October 29, 1901. Acid was placed in the casket to dissolve his body, before burial in the prison graveyard. Czolgosz's actions were politically motivated, although it is unclear what outcome he believed the shooting would yield.

Funeral, memorials, and legacy.

An autopsy was performed later on the morning of McKinley's death; Dr. Mann led a team of 14 physicians. They found the bullet had passed through the stomach, then through the transverse colon, and vanished through the peritoneum after penetrating a corner of the left kidney. There was also damage to the adrenal glands and pancreas. Dr. Herman Mynter, whom the President had met briefly the day before the shooting, who participated in the autopsy, later stated his belief that the bullet lodged somewhere in the back muscles, though this is uncertain as it was never found: after four hours, Ida McKinley demanded that the autopsy end. A death mask was taken, and private services took place in the Milburn House before the body was moved to Buffalo City and County Hall for the start of five days of national mourning.

According to McKinley biographer, Lewis L. Gould, “The nation experienced a wave of genuine grief at the news of McKinley’s passing.” The stock market, faced with sudden uncertainty, suffered a steep decline—almost unnoticed in the mourning. The nation focused its attention on the casket that made its way by train, first to Washington, where it first lay in the East Room of the Executive Mansion, and then in state in the Capitol, and then was taken to Canton. A hundred thousand people passed by the open casket in the Capitol Rotunda, many having waited hours in the rain; in Canton, an equal number did the same at the Stark County Courthouse on September 18. The following day, September 19, the funeral service was held at the First Methodist Church; the casket was then sealed and taken to the McKinley house, on North Market Street, for the last time, where relatives paid their final respects. It was then transported to the receiving vault at West Lawn Cemetery in Canton, to await the construction of the memorial to McKinley already being planned, all activity ceased in the nation for five minutes. Trains came to a halt, telephone and telegraph service was stopped.

There was a widespread expectation that Ida McKinley would not long survive her husband; one family friend stated, as William McKinley lay dying, that they should be prepared for a double funeral. This did not occur; the former first lady accompanied her husband on the funeral train. Leech noted “the circuitous journey was a cruel ordeal for the woman who huddled in a compartment of the funeral train, praying that the Lord would take her with her Dearest Love”. She was not able to attend the services in Washington or Canton, though she listened at the door to the service for her husband in her house on North Market Street. She remained in Canton for the remainder of her life, setting up a shrine in her house, and often visiting the receiving vault, until her death at age 59 on May 26, 1907. She died only months before the completion of the large marble monument to her husband in Canton, which was dedicated by President Roosevelt on September 30, 1907. William and Ida McKinley rest there with their daughters, atop a hillside overlooking the city of Canton.

In addition to the damage done by the bullet, the autopsy also found that the President was suffering from cardiomyopathy (fatty degeneration of the heart muscle). This would have weakened his heart and made him less able to recover from such an injury, and was thought to be related to his overweight frame and lack of exercise. Modern scholars generally believe that McKinley died of pancreatic necrosis, a condition that is difficult to treat today and would have been completely impossible for the doctors of his time.

Other memorials

In addition to the Canton site, for which over a million school children donated money, there are many memorials to William McKinley. There is a monument at his birthplace in Niles; 20 Ohio schools bear his name. Nearly a million dollars was pledged by contributors or allocated from public funds for the construction of McKinley memorials in the year after his death. McKinley biographer, Kevin Phillips suggests that, the significant number of major memorials to McKinley in Ohio reflected the expectation among Ohioans in the years after McKinley’s death that he would be ranked among the great presidents. Statues to him may be found in more than a dozen states; his name has been bestowed on streets, civic organizations, and libraries. Mount McKinley in central Alaska is named for the former president; its summit, at 20,320 feet (6,190 m), is the highest point in North America. Until its name was changed to Denali National Park, the park that surrounds it was known as Mount McKinley National Park.