|

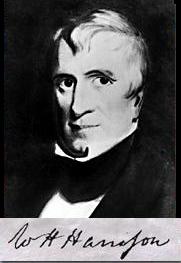

WILLIAM HENRY HARRISON |

|

THE 9TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1841)

HARRISON, William Henry

(1773–1841), ninth president of the U.S. (1841). His claim to fame rests not on his administration—for he died of pneumonia one month after his inauguration—but on the strange campaign by which in 1840 he attained the high office. A minor military hero, he rode to glory by saying nothing (General Mum, his critics called him), while his party, the Whigs, capitalized on a propaganda blunder by their Democratic opponents to proclaim Harrison a simple man used to living in a log cabin.Harrison was born on Feb. 9, 1773, to one of the wealthiest, most prestigious, and most influential families in Virginia, on a great plantation in Berkeley Co. From the early 17th century on, the Harrisons had accumulated vast landholdings, occupied the highest political and judicial positions, and intermarried with the leading families of Virginia. William Henry’s youthful military career and his appointment, when he was not yet 30 years old, to the prominent post of governor of Indiana Territory were due more to the influence of his father, Benjamin Harrison, who had been governor of Virginia, than to any military or administrative talent that he himself had demonstrated.

Military Hero.

Harrison had a modest career that was highlighted by two significant military successes. After devoting his tenure as territorial governor to negotiating the western Indian tribes out of millions of acres, he commanded a force of militia and regulars that put down a Shawnee uprising at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. Although Harrison’s own policies as governor had helped provoke the rebellion, his victory won him a reputation that helped vault him to the presidency a generation later. In the year following the outbreak of the War of 1812, Harrison won another important battle, fought near Canada’s Thames River in the province of Ontario, that ensured continued American control of the western territory.

Although Harrison’s career was moderately successful—he was several times elected to the Ohio Senate and the U.S. House of Representatives—his life at this time was beset by financial difficulties. For a short period in 1828 he served as minister to Colombia, but President John Quincy Adams, who appointed him to the diplomatic post because of his connections, had low regard for Harrison’s ability, and this poor opinion was shared by political figures in Washington, D.C. The nation, however, remembered his military exploits, and in the mid-1830s and again in 1840 Whig party managers decided to exploit them. As one of a number of Whig candidates in 1836, Harrison was an also-ran. In 1840, however, benefiting from the artful campaign tactics of his party, Harrison succeeded.

The 1840 Campaign.

Seeking victory at almost any price, the Whig party in 1840 passed over Henry Clay, its true leader, choosing the aging general instead. To appeal to the South, they chose a states’ rights southern Democrat, John Tyler, as his running mate. Convinced that they could win by blaming the severe economic depression on the policies of President Martin Van Buren, they also derided "Van" for his alleged aristocratic manners, commanded Harrison to be silent on the issues, refused to present a party platform, and waged a rousing campaign, using the slogan "Tippecanoe and Tyler too." Taking advantage of a sneering Democratic reference to Harrison as a man content to sit in his log cabin sipping hard cider, the Whigs’ propaganda transformed the Virginia aristocrat into a poor farmer. Seldom has demagoguery paid off so well.

Perhaps Harrison’s most significant act in his abbreviated term—he died on April 4, 1841—was his appointment of Daniel Webster as secretary of state.