|

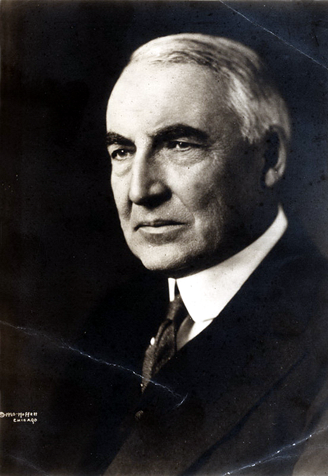

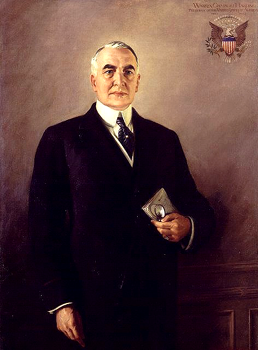

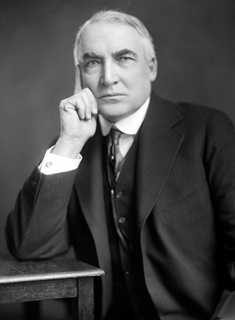

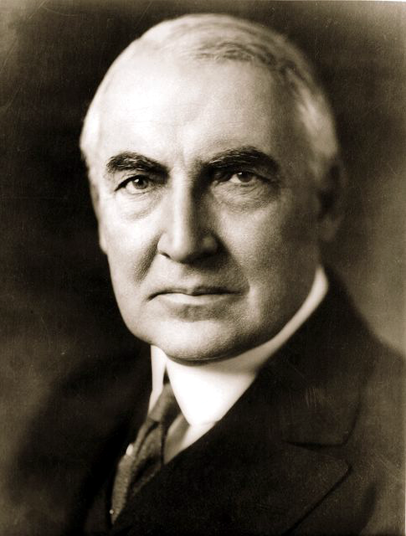

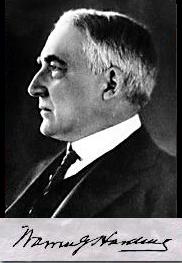

WARREN G. HARDING |

|

THE 29TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1921-1923)

HARDING, Warren Gamaliel

(1865–1923), 29th president of the U.S. (1921–23). He came to office in the aftermath of World War I and voiced a national desire to forego further crusades and a return to "normalcy," but his administration is mainly remembered for its corruption, which was revealed after Harding’s death.

Early Career.

Born in Corsica, Ohio, on Nov. 2, 1865, Harding attended Ohio Central College, studied law, and became editor and publisher of the Marion Star, a country newspaper in Marion, Ohio. After his marriage (1891) to Florence Kling DeWolfe (1860–1924), who was considered a major force in his rise to national prominence, he entered politics as a protégé of Republican Senator Joseph Foraker (1846–1917) and served in the Ohio Senate and as lieutenant governor of the state. He was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1914 but resigned from it in 1920 after winning a landslide election as the Republican candidate for president. At the time of his nomination, and for years afterward, he was widely regarded as having been the choice of the party machine bosses, but more recent scholarship has maintained that Harding simply was the party’s most logical and available nominee.

Harding’s Presidency.

Turning away from the powerful executive leadership style of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson, Harding as president delegated much authority to his cabinet chiefs, whom he chose for their national or regional constituencies or their weight in party councils. Among the outstanding members of his cabinet were Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, and Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace.

Harding’s first presidential task was to move the government away from wartime emergency conditions, and in this his administration was successful. In certain areas it was innovative, stepping up federal hiring during an employment slump, proposing agricultural legislation, and creating a Bureau of the Budget. In 1922 Secretary of State Hughes, with Harding’s active support, scored a diplomatic triumph at the Washington Conference on naval disarmament, when the Great Powers agreed to limit their capital ship tonnage in fixed ratios. Harding also acted forcefully in the movement to limit the long hours of labor that previously had prevailed in the American steel industry.

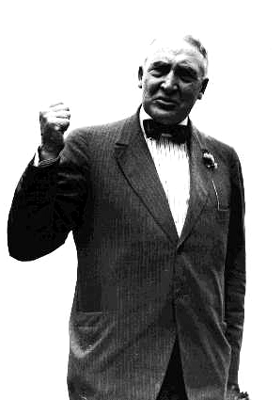

Western travels, illness and death.

In June 1923, Harding set out on a westward cross-country “Voyage of Understanding”, in which he planned to renew his connection with ordinary people, away from the capital, and explain his policies. The schedule included 18 speeches and innumerable informal talks. Accompanying him were Secretaries Work, Wallace, and Hoover, House Speaker Gillett, and Rear Admiral Adam Hugh Rodman. During this trip, he became the first president to visit Alaska.

Harding's physical health had declined since the fall of 1922. One doctor, Emmanuel Libman, who met Harding at a dinner, privately suggested that the President was suffering from coronary disease. By early 1923, Harding had trouble sleeping, looked tired, and could barely get through nine holes of golf.

Though Harding wanted to run for a second term, he may have been aware of his own health decline. He gave up drinking, sold his "life-work," the Marion Star, in part to regain $170,000 previous investment losses, and had the U.S. Attorney General Harry Daugherty make a new will. Harding, along with his personal physician Dr. Charles E. Sawyer, believed getting away from Washington would help relieve the stresses of being President. By July 1923, criticism of the Harding Administration was increasing. Prior to his leaving Washington, the President reported chest pains that radiated down his left arm.

St. Louis, Kansas, Denver

During Harding's western travels, historian Samuel H. Adams claims that Harding's political views began to expand, and became more independent from established Republican Party agenda. In St. Louis, Harding promoted U.S. participation in the World Court having earnestly desired world peace. In Kansas, Harding gave a speech on agriculture and, much to his doctor's displeasure, rode on a farming combine in searing summer heat.

In Denver, Harding extolled the virtues of the 18th Amendment, saying it should never be repealed, urging that the prohibition laws be obeyed. Harding, himself, did not pack any whiskey for traveling on the Presidential train. Breaking away from Republican isolationism, Harding advocated more spending on national defense in case of another war. Harding also made a speech fully endorsing labor's right to organize, and even spoke against those who sought to destroy labor movements around the country. In Tacoma, Washington, the President read a letter that promoted his efforts for a 12-hour work day. Sensing his own conversion, Harding even told his friends that he felt a spiritual change was influencing his stance on issues.

Alaska, British Columbia, Seattle

President Harding, as his physically demanding schedule continued, boarded a naval transport ship, the USS Henderson, and voyaged to Alaska. During four days at sea, Harding was unable to rest and regain strength. Rumors of corruption in his administration were beginning to circulate in Washington. While in Alaska, Harding was profoundly shocked by a long message he received detailing illegal activities previously unknown to him.

Harding's reasons for the Alaska visit included encouraging colonization of the sparsely populated territory. Harding hoped that, with completion of the Alaska Railroad, World War I veterans from Alaska would return to their home territory, and impoverished workers in the lower states could go to Alaska for employment. Harding brought along Secretary of Interior Hubert Work, Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover, and Secretary of Agriculture Henry C. Wallace—"the three bears", as Herbert Hoover called them—to cut through bureaucracy in their respective departmental jurisdictions.

According to author Douglas Brinkley, Harding came to the most northern U.S. territory to "open up Alaska lands" for oil, mining, timber development, and industry.

Harding arrived in Alaska on the USS Henderson on July 7, 1923. Harding and his presidential party first visited Metlakatla, Ketchikan (July 8), and Wrangell (July 9). They continued on to Juneau (July 10), Skagway, and Glacier Bay (July 11). The President then cruised to Seward (July 13). They then proceeded to travel by Presidential railway car and automobile. Harding visited Snow River on the Kenai Peninsula, Anchorage (July 13), Chickaloon, Wasilla and Willow (July 14). The U.S. government had bought up the financially unstable Tanana Valley Railroad. The President continued his Alaska journey through Montana Station, Curry (July 14) Cantwell, McKinley Park and Nenana(July 15). On July 15, 1923, Harding drove in the golden spike on the north side of the steel Mears Memorial Bridge that completed the Alaska Railroad. The trip continued to Fairbanks (July 15) where it was decided (July 16) that the President and his wife would return to Seward (July 17) via the railroad. They spent a restful day at Seward (July 18). From there they took the Henderson to Valdez (July 19), Cordova (July 20), and Sitka (July 22). While in Sitka, Harding visited and shook hands with Alaskan Native Tlingit elder chief Katlean outside in a crowd of people. The information gathered by Harding's Alaska tour found that improving agriculture in south central Alaska, would require irrigation because of the low territory rainfall totals. By 1923, the Alaskan salmon population was being depleted from overfishing. Harvesting and transporting coal by ship from Alaska through the territory's panhandle would be very expensive.

On July 26, 1923, having departed Alaska on the USS Henderson, Harding toured Vancouver, British Columbia as the first sitting American President ever to visit Canada. Harding became exhausted while playing golf at the Shaughnessy Heights Golf Club, and complained of nausea and upper abdominal pain. His doctor, Charles E. Sawyer, believed Harding's illness was a severe case of food poisoning. Nevertheless, Dr. Joel T. Boone also examined the President and noticed an enlargement of his heart. Harding's pulse and breathing rate were rapid. The President was given digitalis. Harding met with British Columbia Premier John Oliver and Mayor of Vancouver Charles Tisdall at the Hotel Vancouver. Harding spoke in front of 50,000 people at Stanley Park with his voice projected by microphones. Harding inspected The Vancouver Regiment honor guard accompanied by Canadian Brig. Gen. V.W. Odlum. There is a monument to President Harding in Vancouver's Stanley Park.

Coming into Seattle, Washington, Harding's transport ship, USS Henderson, accidentally rammed into the USS Zeilin (DD-313), a U.S. naval destroyer, due to fog. Harding was not harmed in the incident. While in port, Harding reviewed the U.S. naval fleet and visited the Bell Street Pier. In Seattle, Harding greeted children and led 50,000 Boy Scouts in the Pledge of Allegiance. Harding gave his final speech to a large crowd of 25,000 people at the University of Washington stadium (now Husky Stadium), in Seattle, Washington. Harding spoke on the magnificence of Alaska's wilderness, conservationism, and "measureless oil resources in the most northerly sections." Sec. of Commerce Herbert Hoover wrote the Seattle speech and Harding claimed he would protect the territory from looters and profit seekers; a rebuff to former Sec. of Interior Albert Fall. Harding had rushed through his speech not waiting for applause by the audience. Harding traveled by train from Seattle to Portland, Oregon. Harding's scheduled speech in Portland was canceled.

Death in San Francisco, state funeral and memorial

The President's train proceeded south to San Francisco. Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover sent a telegram from Dunsmuir, California, to his friend Dr. Ray L. Wilbur, asking Wilbur to meet and to personally evaluate the President. Upon arriving at the Palace Hotel in San Francisco, Harding developed a respiratory illness believed to be pneumonia. Harding, severely exhausted, ordered that his planned speech be issued through the national press in order to communicate with the public. The President was given digitalis and caffeine that momentarily helped relieve his heart condition and sleeplessness. On Thursday, the President's health appeared to improve, so his doctors went to dinner. Harding's pulse was normal and his lung infection had subsided. Unexpectedly, during the evening, Harding shuddered and died suddenly in the middle of conversation with his wife in the hotel's presidential suite, at 7:35 p.m. on August 2, 1923. Surgeon General, Dr. Charles E. Sawyer (a homeopath, and friend and personal medical advisor of the Harding family), opined that Harding had succumbed to a stroke, but doctors there disagreed.

Immediately after Harding died, word of the event quickly spread to the San Francisco streets. People rushed into the Palace Hotel, and rapidly crowded into the hallways. The San Francisco chief of police, Daniel J. O'Brian, finally was able to clear the hotel of the unruly mob, and members of Harding's official party could come see him.

After some discussion, the doctors issued a release stating that the cause of death was "some brain evolvement, probably an apoplexy." The formal announcement, printed in the New York Times of that day, stated that "A stroke of apoplexy was the cause of death." He had been ill exactly one week. Mrs. Harding refused to allow an autopsy. In retrospect, scholars speculate that Harding had shown physical signs of cardiac insufficiency with congestive heart failure in the preceding weeks. Naval medical consultants who examined the president in San Francisco concluded he had suffered a heart attack. Dr. Wilbur included in his memoirs a letter from Dr. Charles Miner Cooper in support of their cerebral apoplexy diagnosis, based on Harding's last observed condition, while acknowledging that no final determination could be made.

Harding was succeeded as President by Vice President Calvin Coolidge, who was sworn in while vacationing at Plymouth Notch, Vermont, by his father, a Vermont notary public.

A story of Harding's body being laid in state in San Francisco City Hall before being returned to Washington is apparently false. The Examiner for Aug. 3, 1923, states that Harding's "remains will not be taken from the hotel except to go directly to the train." The Chronicle for Aug. 3 and 4, 1923, says the same thing, that Harding's body was taken from the Palace Hotel directly to the train depot at Third and Townsend. The funeral train made a four-day journey eastward across the country—the first such procession since Lincoln's funeral train. Millions lined the tracks in cities and towns across the country to pay their respects.

Harding's casket was placed in the East Room of the White House pending a state funeral, which was held on August 8, 1923, at the United States Capitol. Unnamed White House employees said that the night before the funeral, they heard Mrs. Harding talking to her dead husband. According to the historian Samuel H. Adams, Harding's death was mourned by the nation and the average citizen felt a "personal loss." Harding was entombed in the receiving vault of the Marion Cemetery, Marion, Ohio, on August 10, 1923. Following Mrs. Harding's death on November 21, 1924 (from renal failure), she was buried next to her husband. Their remains were re-interred December 20, 1927, at the newly completed Harding Memorial in Marion, dedicated by President Herbert Hoover on June 16, 1931. The delay between final interment and the dedication was partly because of the aftermath of the Teapot Dome scandal. Harding was survived by his father Dr. George Tryon Harding, who died on November 19, 1928. Harding and John F. Kennedy are the only two presidents to have predeceased their fathers. Harding's term of office was the shortest of any 20th-century U.S. President.

Speculation on cause of death.

Harding's sudden death led to theories that he had been poisoned or committed suicide. Suicide appears unlikely, since Harding was planning for reelection in 1924. Rumors of poisoning were fueled, in part, by a book called The Strange Death of President Harding (1930), in which the author (convicted criminal, former Ohio Gang member, and detective Gaston Means, hired by Mrs. Harding to investigate Warren Harding and his mistress) suggested that Mrs. Harding had poisoned her husband. Mrs. Harding's refusal to allow an autopsy on her husband only added to the speculation. Several individuals attached to Harding, personally and politically, would have welcomed Harding's death, as they would have been disgraced in association by Means' assertion of Harding's "imminent impeachment." Means was later discredited for publicly accusing Mrs. Harding of the purported murder.

According to the physicians attending Harding, however, the symptoms prior to his death all pointed to congestive heart failure. Harding's biographer, Samuel H. Adams, concluded that "Warren G. Harding died a natural death which, in any case, could not have been long postponed".

Presidential papers destroyed.

Immediately after Harding's death, Mrs. Harding returned to Washington, D.C., and briefly stayed in the White House with President and First Lady Coolidge. For a month, former First Lady Harding gathered and burned President Harding's correspondence and documents, both official and unofficial. Upon her return to Marion, Mrs. Harding hired a number of secretaries to collect and burn Harding's personal papers. According to Mrs. Harding, she took these actions to protect her husband's legacy. The remaining papers were held and kept from public view by the Harding Memorial Association in Marion.

The Scandals.

In the months that followed Harding’s death, charges of misconduct in the Interior and Navy departments, the Veterans’ Bureau, the Justice Department, and the Office of the Alien Property Custodian were disclosed in a series of congressional investigations and criminal trials. The scandals implicated both high officials and personal friends of Harding. Among those indicted were Attorney General Harry M. Daugherty (1860–1941) and Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall. Fall was eventually convicted of taking bribes and was sent to jail. Revelations of bribery, influence peddling, and outright theft overshadowed the positive achievements of the Harding administration. The president had spoken all too truly when he remarked that he could take care of his enemies but that he did not know how to cope with his friends.