|

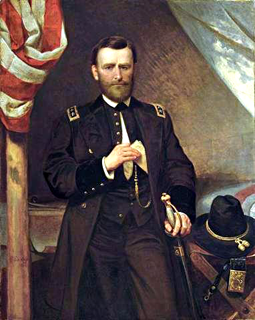

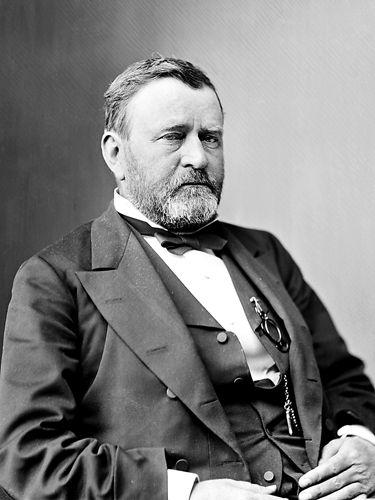

ULYSSES S. GRANT |

|

THE 18TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1869-1877)

GRANT, Ulysses S(impson)

(1822–85), American general and 18th president of the U.S. (1869–77).Grant was born at Point Pleasant, Ohio, on April 27, 1822, the son of Hannah Simpson (1798–1883) and Jesse Grant (1794–1873), the owner of a tannery. Taken to nearby Georgetown at the age of one year, he was educated in local and boarding schools. In 1839, under the name of Ulysses Simpson instead of his original Hiram Ulysses, he was appointed to West Point. Graduating 21st in a class of 39 in 1843, he was assigned to Jefferson Barracks, Mo. There he met Julia Dent (1826–1902), a local planter’s daughter, whom he married after the Mexican War.

Prewar Career.

During the Mexican War, Grant served under both Gen. Zachary Taylor and Gen. Winfield Scott and distinguished himself, particularly at Molina del Rey and Chapultepec. After his return and tours of duty in the North, he was sent to the Far West. In 1854, while stationed at Fort Humboldt, Calif., Grant resigned his commission because of loneliness and drinking problems, and in the following years he engaged in generally unsuccessful farming and business ventures in Missouri. He moved to Galena, Ill., in 1860, where he became a clerk in his father’s leather store.

The Civil War.

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Grant was appointed colonel, and soon afterward brigadier general, of the Illinois Volunteers, and in September 1861 he seized Paducah, Ky. After an inconclusive raid on Belmont, Mo., he gained fame when in February 1862, in conjunction with the navy, he succeeded in reducing Forts Henry and Donelson, Tenn., forcing Gen. Simon B. Buckner to accept unconditional surrender. The Confederates surprised Grant at Shiloh (April 1862), but he held his ground and then moved on to Corinth. In 1863 he established his reputation as a strategist in the brilliant campaign against Vicksburg, Miss., which capitulated on July 4. After being appointed commander in the West, he defeated Braxton Bragg at Chattanooga (November 1863). Grant’s victories made him so prominent that he was promoted to the rank of lieutenant general and in February 1864 was given command of all Union armies.

Grant’s subsequent campaigns revealed his determination to apply relentless pressure against the Confederacy by coordinating the Union armies and exploiting the economic strength of the North. While Grant accompanied the Army of the Potomac in its overland assault on Richmond, Va., Gen. Benjamin F. Butler was to attack the city by water, Gen. William T. Sherman to move into Georgia, and Gen. Franz Sigel (1824–1902) to clear the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Despite the failure of Butler and Sigel and heavy losses at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor, Grant continued to press the drive against Gen. Robert E. Lee’s army. After Sherman’s success in Georgia and the conquest of the Shenandoah Valley by Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, Grant forced Lee to abandon Petersburg and Richmond (April 2, 1865) and to surrender at Appomattox Court House on April 9.

Road to the Presidency.

As commander of the army, Grant soon became enmeshed in the struggles between President Andrew Johnson and Congress. Because of the president’s evident pro-Southern tendencies, the general gradually moved closer to the radicals and cooperated with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in carrying out the congressional Reconstruction plan for the South. Grant accepted appointment as secretary ad interim after Johnson’s dismissal of Stanton, but clashed violently with the president when the Senate ordered Stanton reinstated. Then, as the country’s best-known military leader, he became the Republican candidate for president in 1868 and defeated his Democratic rival, Horatio Seymour.

The Presidency.

Grant’s military experience ill prepared him for his new duties. Faced with major problems of Reconstruction, civil service reform, and economic adjustment, he did not know how to choose proper advisers or to avoid the pitfalls of an age of corruption. Encouraged by the final restoration of all the Southern states to the Union, he honestly tried to carry out congressional Reconstruction, but in the long run was unable to sustain it. Intermittently trying to protect the rights of the freed slaves, he repeatedly intervened but could not prevent the resurgence of white supremacists in all but a few Southern states.

Other problems were equally troublesome. In 1871 Grant appointed a civil service commission headed by George W. Curtis (1824–92) but because of the president’s increased reliance on corrupt Republican machines, he was ill fitted to end the system whereby federal jobs were distributed as rewards for political loyalty. Moreover, his inexperience in economic matters and his inordinate respect for wealth rendered him easy prey to scheming adventurers. Thus, in 1869 he was taken in by Jay Gould and James Fisk in their attempt to corner the gold market, which he stopped only at the last moment. In 1872 dissident reformers, breaking with the administration by organizing the Liberal Republican party, nominated Horace Greeley, who also received the Democrats’ endorsement, to challenge Grant for reelection. Although the president won easily, his second administration was besmirched by many scandals, including the Crédit Mobilier affair, in which Vice-President Schuyler Colfax and others were accused of taking bribes; the Whiskey Ring, in which Grant’s secretary connived with a group of distillers to defraud the government of taxes; and the impeachment of Secretary of War William W. Belknap (1829–90). All contributed to the failure of the administration. In addition, the Panic of 1873 resulted in widespread unemployment and the loss of the House of Representatives to the Democrats.

Only in foreign affairs did Grant have some success. He suffered an initial setback in the Senate, which refused to sanction his dubious scheme to purchase Santo Domingo. Thereafter, however, Secretary of State Hamilton Fish established a distinguished record by settling outstanding difficulties with Great Britain (Treaty of Washington, 1871) and keeping the country clear of the Cuban rebellion against Spain.

Final Years.

After retiring from the presidency, Grant took a long trip around the world. Returning in 1879, he became an unsuccessful contender for the presidential nomination, which went to James A. Garfield. In 1881 Grant moved to New York City, where he became a partner in the Wall Street firm of Grant and Ward; he was close to ruin when the company collapsed in 1884. To provide for his family, he wrote his memoirs while fighting cancer of the throat; he died at Mount Gregor, N.Y., on July 23, 1885.

A military genius, Grant possessed the vision to see that modern warfare requires total application of military and economic strength and was thus able to lead the Union to victory. In civilian life, however, he was unable to provide the leadership necessary for a burgeoning industrial nation, even though he always retained the affection of the American public.