|

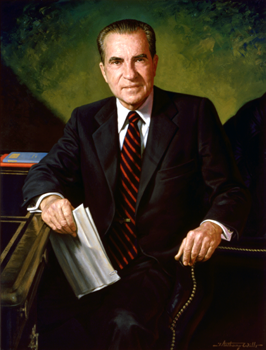

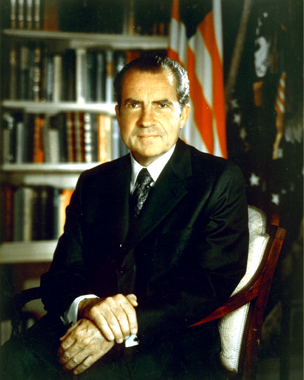

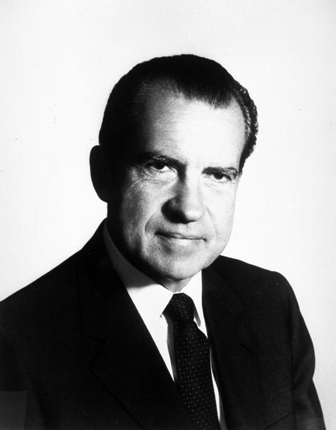

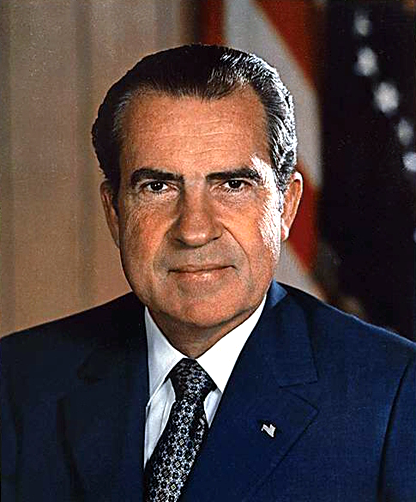

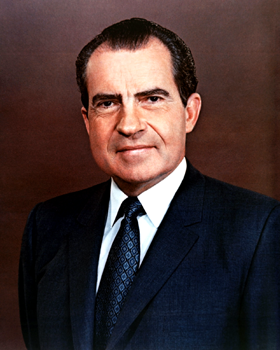

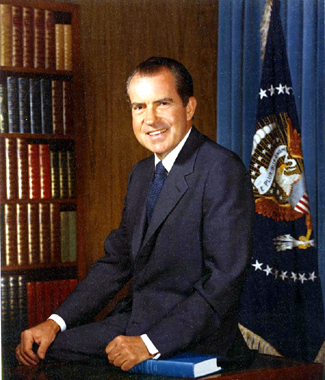

RICHARD NIXON |

|

THE 37TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1969-1974)

NIXON, Richard Milhous

(1913–94), 37th president of the U.S. (1969–74), and the only one to have resigned from office.Nixon was born in Yorba Linda, Calif., on Jan. 9, 1913. His parents were poor, and his early life was one of hard work and study. He was a gifted student, finishing second in his class at Whittier College (1934) in Whittier, Calif., and third in his class at Duke University Law School (1937). Unable to find a position with a Wall Street (New York City) law firm after his graduation, Nixon returned to Whittier to practice. There he met Thelma Catherine (Pat) Ryan (1912–93), whom he married in 1940. Nixon enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1942 and served as a supply officer in the South Pacific during World War II. He left the service as a lieutenant commander.

Back in Whittier in 1946, Nixon was persuaded by a group of southern California Republicans to challenge Democratic congressman Jerry Voorhis (1901–84). Nixon campaigned vigorously, tabbed the liberal Voorhis as a dangerous left-winger, and won by 16,000 votes. In 1948 and 1949 Nixon achieved a national reputation in the U.S. House of Representatives as a member of the Committee on Un-American Activities during its investigation of what became known as the Hiss case. In 1950 Nixon ran for the U.S. Senate and won against Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas (1900–80), whom he labeled the "Pink Lady" for what he alleged to be her pro-Communist sympathies; his campaign tactics were widely criticized.

Vice-President.

In 1952 the Republicans nominated Nixon to be the running mate of presidential candidate Dwight D. Eisenhower. When it was disclosed that as a senator Nixon had accepted an $18,000 fund for "political expenses" from California businessmen, he was nearly dropped from the Republican ticket. Nixon’s televised self-defense, called the "Checkers" speech because of a sentimental reference to his dog Checkers, saved his political life. As vice-president, Nixon emerged as a vigorous Republican spokesman during the Eisenhower years, campaigning in a cut-and-thrust style that contrasted with Eisenhower’s nonpartisan aloofness. In nonelection years, Nixon toured the country trying to bolster Republican party finances and spirit. He also developed foreign affairs credentials by visiting numerous other countries, including the Soviet Union, where an impromptu "kitchen debate" with Nikita S. Khrushchev made worldwide headlines in July 1959. As undisputed party leader at the end of Eisenhower’s second term, Nixon easily won the presidential nomination in 1960. Against the articulate, wealthy, and politically well-connected John F. Kennedy, however, the Nixon edge in experience and prominence melted away. Kennedy won with a narrow popular-vote margin of 113,000 votes out of 68.8 million cast.

Returning to California, Nixon sought to revitalize his political career by challenging Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown (1905–96) in the 1962 gubernatorial race. Defeated, Nixon angrily announced his withdrawal from active politics. He moved to New York City and began a lucrative law practice. He continued, however, to speak out on foreign policy issues, address Republican fund rallies, and maintain his strong influence in the party. By 1968 he was poised again to try for the presidency, this time as a more temperate "new Nixon." With Spiro T. Agnew as the vice-presidential candidate, the Republican campaign made skillful use of television, and benefited from national dissatisfaction with the war in Vietnam and from division in the Democratic camp. Nixon defeated Hubert H. Humphrey with a popular-vote majority of about 500,000 votes.

President.

At the pinnacle of his career in 1969, President Nixon organized the White House to protect his energy and time. He left most administrative affairs to such powerful aides as H(arry) R(obbins) Haldeman (1926–93), John Ehrlichman (1925–99), and Charles Colson (1931– ). This allowed him time for what had become his absorbing interest: international affairs. With Henry A. Kissinger as his most trusted foreign policy adviser, Nixon redefined the American role in the world, suggesting limits to U.S. resources and commitments. "After a period of confrontation," he declared in his inaugural address, "we are entering an era of negotiation." He ordered a gradual withdrawal of the 500,000 U.S. troops in South Vietnam. The withdrawal took four years, however, during which the war raged and U.S. casualties mounted. Nixon authorized a U.S. incursion into Cambodia in 1970 and the bombing of Hanoi and the mining of Haiphong Harbor in 1972. These actions were unpopular, but he credited them with helping to bring about a negotiated settlement by which all U.S. forces were withdrawn and all known U.S. prisoners of war released before the end of March 1973.

Nixon’s greatest innovation was his approach to the People’s Republic of China. Sensing that the time was right to make an overture to China, Nixon sent Kissinger to confer secretly with Chinese premier Zhou Enlai in July 1971. Nixon’s own 1972 summit meeting in China, at which he signed the Shanghai Communiqué, was a diplomatic triumph that left the president’s critics, accustomed to his fervent anti-Communism, astonished and off-balance. Within a few weeks, Nixon was in Moscow to negotiate the first step in a strategic arms limitation agreement. Born in that session was the era of détente, a search for accommodation between the two superpowers, and an effort to reduce the danger of nuclear war.

Other parts of the world were not neglected. In the strategically vital Middle East, Nixon established links with Egypt while maintaining the U.S. commitment to Israel. After the Yom Kippur War of 1973, the U.S. replaced the Soviet Union as the dominant influence in Egypt.

At home, Nixon adopted the so-called New Federalism, a program designed to end what he said was the Democratic habit of "throwing money at problems." Congress passed part of the plan—revenue sharing with states and cities—and appropriated some $30 billion for local needs. While espousing the fiscal conservatism traditional to his party, Nixon held to no set economic course. After first advocating a balanced budget, he turned to deficit financing. Having decided against wage and price controls to battle rising inflation rates, he reversed himself dramatically in August 1971. He imposed controls, with limited success, in four phases extending into 1974. Nixon’s economic policies were bold but inconsistent, and, partly because of rapidly rising energy costs, he was unable to avert a recession in 1974.

On racial matters, Nixon generally adopted a passive stance toward efforts by American blacks to achieve educational, economic, and social equality. He personally opposed busing but insisted that the law be upheld in cases where the courts required it.

The Nixon response to rising urban crime rates included demands for stricter law enforcement and less "coddling" of criminals and radical activists. The leading voice for this politically popular theme of "law and order" was Attorney General John N. Mitchell, the president’s former law partner and campaign manager. Nixon’s four Supreme Court appointees, men whom he called "strict constructionists," brought a more conservative cast to the Court. They were Chief Justice Warren Burger and Justices Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, Jr., and William Rehnquist.

Watergate and Resignation.

Up for reelection in 1972, Nixon was fresh from the Beijing and Moscow triumphs and enjoying the peak of his popularity. He defeated the Democratic senator George S. McGovern by one of the largest majorities in U.S. history. Only one small cloud appeared on the horizon. The attempted burglary and wiretapping of the Democratic National Committee headquarters on June 17, 1972, at the Watergate complex had been traced to men hired by some of the president’s closest advisers. Newspaper reporters took the slender thread found at the Watergate burglary and followed it to the White House. Through determined reporting, a larger picture of political corruption was uncovered. Illegal campaign contributions, political "dirty tricks," and irregularities in Nixon’s income taxes were unearthed as the story grew during 1973. Testimony before the Senate Select. Committee on Presidential Campaign Activities, chaired by Senator Sam Ervin, Jr. (1896–1985), revealed that extensive tape recordings existed of conversations held in Nixon’s office. The various investigations, including that by Archibald Cox (1912–2004), who was appointed special prosecutor for the case in May 1973, began to focus on the release of these vital tapes.

Public trust in Nixon’s leadership plummeted after he had Cox dismissed in October 1973. To compound the president’s problems, Vice-President Agnew, facing bribery charges, resigned in the same month. In his choice of a replacement, Nixon settled on a popular U.S. congressman certain of quick confirmation: Gerald R. Ford of Michigan, who was sworn in as vice-president on Dec. 6, 1973.

A federal grand jury named the president in March 1974 as an unindicted coconspirator in a conspiracy to obstruct justice in the Watergate investigation. Attorney Leon Jaworski (1905–82), who replaced Cox as special Watergate prosecutor, continued to press for the White House tapes, while the House Judiciary Committee began to investigate the case for impeachment.

Nixon tried to reestablish his authority with trips to the Middle East and the Soviet Union in the summer of 1974. But the Watergate net closed tighter upon his return. On July 24, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the president had to turn over the last tapes. One of these, recording his order to the Federal Bureau of Investigation to halt its investigation of the Watergate break-in, was conclusive evidence—the so-called smoking gun—of Nixon’s primary role in a cover-up. The Judiciary Committee recommended impeachment to the full House of Representatives. On the evening of August 8, Nixon went on television to announce his decision, unprecedented in U.S. history, to resign. At noon on August 9, Gerald Ford took the oath of office.

Pardoned by his successor "for all offenses against the United States which he . . . committed or may have committed" in office, Nixon in retirement initially kept a low profile. Gradually, however, through a succession of TV interviews, memoirs, and writings on world affairs, he rebuilt his reputation as a political analyst and foreign policy expert.

Assassination attempts & plots.

April 13, 1972: Arthur Bremer carried a firearm to an event intending to shoot Nixon, but was put off by strong security. A few weeks later, he instead shot and seriously injured Governor of Alabama George Wallace.

February 22, 1974: Samuel Byck planned to kill Nixon by crashing a commercial airliner into the White House. He hijacked the plane on the ground by force, and was told that it could not take off with the wheel blocks still in place. After he shot the pilot and copilot, an officer shot Byck through the plane's door window. He survived long enough to kill himself by shooting. These events were portrayed in the film The Assassination of Richard Nixon.

Death and funeral.

Nixon suffered a severe stroke on April 18, 1994, while preparing to eat dinner in his Park Ridge home. A blood clot resulting from his heart condition had formed in his upper heart, broken off, and traveled to his brain. He was taken to New York Hospital–Cornell Medical Center in Manhattan, initially alert but unable to speak or to move his right arm or leg. Damage to the brain caused swelling (cerebral edema), and Nixon slipped into a deep coma. He died at 9:08 p.m. on April 22, 1994, with his daughters at his bedside. He was 81 years old.

Nixon's funeral took place on April 27, 1994. Eulogists at the Nixon Library ceremony included President Bill Clinton, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, Senate Minority Leader Bob Dole, California Governor Pete Wilson, and the Reverend Billy Graham. Also in attendance were former Presidents Ford, Carter, Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and their wives.

Richard Nixon is buried beside his wife Pat on the grounds of the Nixon Library, in Yorba Linda, California. He was survived by his two daughters, Tricia and Julie, and four grandchildren. In keeping with his wishes, his funeral was not a full state funeral, though his body did lie in repose in the Nixon Library lobby from April 26 to the morning of the funeral service. Mourners waited in line for up to eight hours in chilly, wet weather to pay their respects. At its peak, the line to pass by Nixon's casket was three miles long with an estimated 42,000 people waiting to pay their respects.

Pat Nixon died on June 22, 1993, of emphysema and lung cancer. Her funeral services were held on the grounds of the Richard Nixon Library and Birthplace. Former President Nixon was distraught throughout the interment and delivered a moving tribute to her inside the library building.

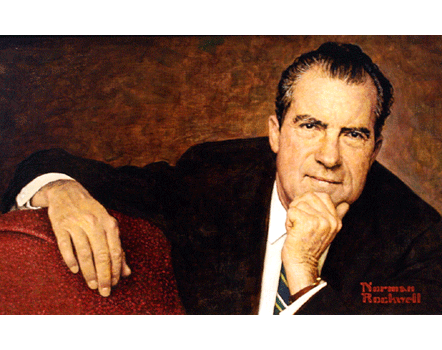

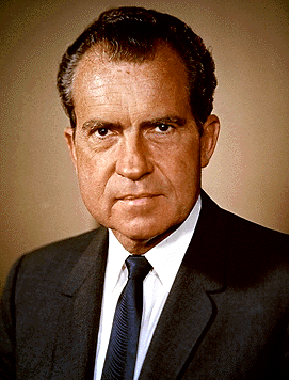

John F. Stacks of Time magazine said of Nixon shortly after his death, "An outsize energy and determination drove him on to recover and rebuild after every self-created disaster that he faced. To reclaim a respected place in American public life after his resignation, he kept traveling and thinking and talking to the world's leaders ... and by the time Bill Clinton came to the White House [in 1993], Nixon had virtually cemented his role as an elder statesman. Clinton, whose wife served on the staff of the committee that voted to impeach Nixon, met openly with him and regularly sought his advice." Tom Wicker of The New York Times noted that Nixon had been equalled only by Franklin Roosevelt in being five times nominated on a major party ticket and, quoting Nixon's 1962 farewell speech, wrote, "Richard Nixon's jowly, beard-shadowed face, the ski-jump nose and the widow's peak, the arms upstretched in the V-sign, had been so often pictured and caricatured, his presence had become such a familiar one in the land, he had been so often in the heat of controversy, that it was hard to realize the nation really would not 'have Nixon to kick around anymore'." Ambrose said of the reaction to Nixon's death, "To everyone's amazement, except his, he's our beloved elder statesman."

Upon Nixon's death, almost all of the news coverage mentioned Watergate, but for the most part, the coverage was favorable to the former president. The Dallas Morning News stated, "History ultimately should show that despite his flaws, he was one of our most farsighted chief executives." This offended some; columnist Russell Baker complained of "a group conspiracy to grant him absolution". Cartoonist Jeff Koterba of the Omaha World-Herald depicted History before a blank canvas, his subject Nixon, as America looks on eagerly. The artist urges his audience to sit down; the work will take some time to complete, as "this portrait is a little more complicated than most"