|

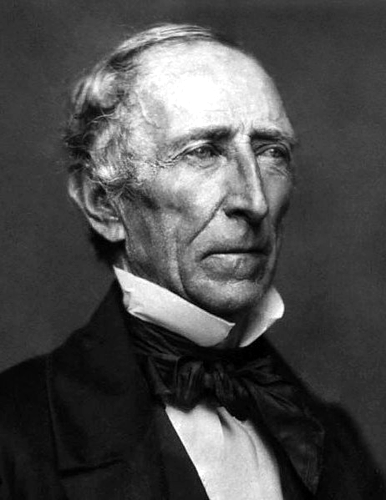

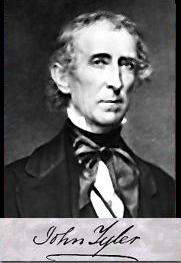

JOHN TYLER |

|

THE 10TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1841-1845)

TYLER, John

(1790–1862), tenth president of the U.S. (1841–45); he was the first vice-president to succeed to the office on the death of a president. Tyler was an independent who refused to compromise on principles to please political allies. The son of John Tyler (1747–1813), an American Revolution patriot who served three terms as governor of Virginia, Tyler was born in Charles City Co., Va., on March 29, 1790. After completing his legal studies, he entered politics, devoted to Thomas Jefferson’s principles of states’ rights and strictly limited power for the federal government. At the age of 21 he was elected to the Virginia legislature and in 1816 was chosen for the U.S. House of Representatives, serving there for four years. After returning to the state legislature for a brief stint, Tyler followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming governor of Virginia in 1825. Two years later he was elected to the U.S. Senate. Although a Democrat, he opposed his party’s leader, President Andrew Jackson, when Jackson forced South Carolina to accept a federal tariff in 1832, and he voted to censure the president for removing deposits from the Bank of the United States in 1834. Two years later he resigned from the Senate rather than succumb to party pressure to reverse himself on the censure. The Whig party, hoping to broaden its electoral appeal, chose this independent-minded Democrat as William Henry Harrison’s running mate in the presidential election of 1840. Adding to Tyler’s appeal to the Whigs was his known admiration of Henry Clay, the Whig leader in the Senate.

Tyler as President.

When the victorious Harrison died a month after his inauguration, and Tyler succeeded him, Clay assumed that the new president would cooperate in passing legislation favored by the Whigs. He and the Whig leadership were therefore infuriated when Tyler vetoed two successive Whig-sponsored bills that would have allowed a national bank to open branches in the states without state consent. Because he was the first person to occupy the presidency without having been elected to the office, they began to refer to him contemptuously as "His Accidency" and contended that he was only an acting president. The strong-minded Tyler, however, insisted that he was president in the full sense of the word; an attempt to impeach him failed to win the necessary votes. When the members of his cabinet—most of whom were Clay supporters—quit their positions, Tyler replaced them with men of his own choosing. The one holdover was Daniel Webster, who, as secretary of state, negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with Great Britain in 1842, resolving a dispute between the U.S. and Canada. The most significant domestic measure of Tyler’s single term was the Preemption Act of 1841, which gave squatters on government lands the right to buy 160 acres (about 65 ha) at the minimum auction price, without competitive bidding. He actually had little to do with the passage of this law. Literally a man without a party, his last act as president was to sign the bill providing for the annexation of Texas.

Postpresidential Career.

Some Democrats nominated Tyler for reelection in 1844, but he stepped aside for James K. Polk, the official party candidate. In his later years Tyler remained a strong advocate of states’ rights. A member of the Virginia convention elected to consider secession on the eve of the American Civil War, he voted for withdrawal from the Union and served briefly in the Confederate Congress before he died in Richmond on Jan. 18, 1862.