|

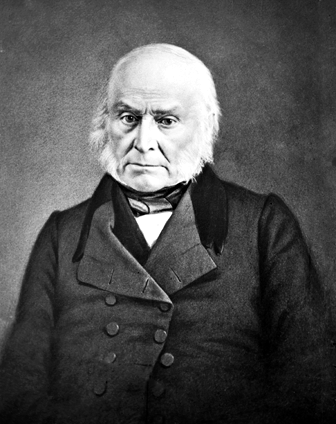

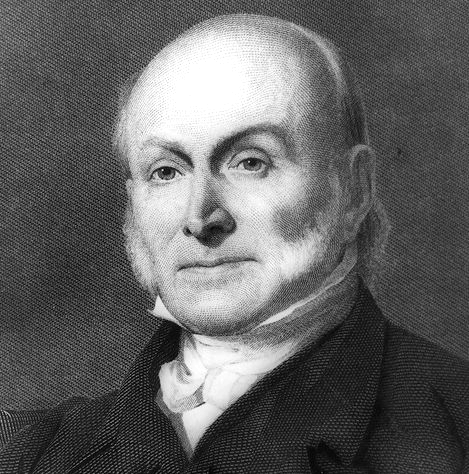

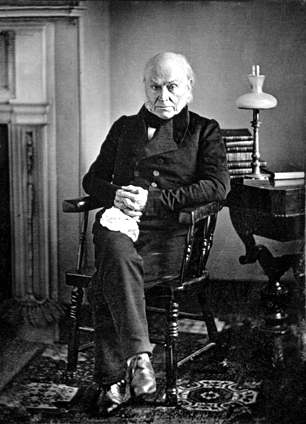

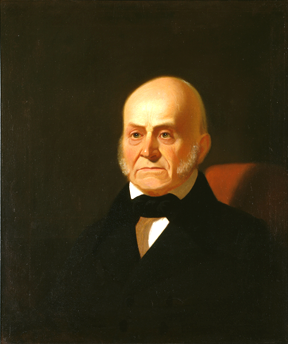

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS |

|

THE 6TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1825-1829)

ADAMS, John Quincy

(1767–1848), sixth president of the U.S. (1825–29), who combined brilliant statesmanship with skillful diplomacy. As secretary of state (1817–25) he ranks among the ablest holders of the office, and he played a major role in formulating American foreign policy. As an eight-term member of the House of Representatives (1831–48) he was a leading defender of freedom of speech and a spokesman for the antislavery cause.

Early Career.

Adams was born in Braintree (now Quincy), Mass., on July 11, 1767, the eldest son of John and Abigail Adams. Remarkably precocious, at the age of 12 he accompanied his father to Europe. He served as French translator to Francis Dana (1743–1811), U.S. minister to Russia, in 1781–83 and as his father’s secretary in 1783, during the peace negotiations that ended the American Revolution. He graduated from Harvard College and opened a law office in Boston.

Adams’s "Publicola" essays, attacking the views Thomas Paine expressed in the Rights of Man, won him early political recognition. In 1793 President George Washington named him minister to Holland and then sent him to London to aid John Jay in negotiations with the British. In London he met Louisa Catherine Johnson (1775–1852), whom he married in 1797; it was a happy union, marked by deep affection. That same year he became minister to Prussia, with which he concluded a pact incorporating the neutral rights provisions of Jay’s Treaty.

In 1801 Adams was elected to the Masssachusetts Senate and two years later to the U.S. Senate. Although a Federalist, he followed an independent course. Adams supported the Louisiana Purchase. This and his endorsement of President Thomas Jefferson’s policy of commercial warfare led to a break with his party and his resignation in 1808. The following year President James Madison appointed him minister to Russia, where he did much to encourage Czar Alexander’s friendly feelings toward the U.S. As one of the delegates sent to Ghent to negotiate an end to the War of 1812, Adams found the British commissioners so intransigent that he had to approve a peace treaty (1814) that fell short of U.S. expectations. In 1815 he was appointed minister to Great Britain, where he did much to ease tensions resulting from the war.

Secretary of State.

In 1817 President James Monroe chose Adams as his secretary of state, inaugurating a long and harmonious association, for the two men agreed on basic foreign policy aims. Both were expansionists, and both wanted the U.S. to follow a course distinct from that of the European powers. Monroe closely controlled foreign policy but relied heavily on the advice of Adams, who was an adroit negotiator. Adams’s state papers are among the most brilliant ever penned by a secretary of state. With Monroe’s support, he forced Spain to cede Florida and to make a favorable settlement of the Louisiana boundary in the Transcontinental Treaty drafted in 1819. His protracted negotiations with the French minister on outstanding issues between the two countries were less successful. The treaty concluded in 1822 only provided for a gradual reduction of France’s discriminatory tariff, leaving other questions unsettled. His efforts to persuade Great Britain to open its West Indian trade to American ships were unsuccessful.

Adams did not share Monroe’s apprehension that the European powers might intervene to suppress the South American revolutions and restore Spain’s authority in its colonies. He was concerned, however, about Russian expansion on the west coast and thus welcomed Monroe’s decision to formulate in his annual message of December 1823 a declaration (later known as the Monroe Doctrine) expressing American opposition to European intervention in the Americas. At Adams’s suggestion, Monroe added a statement declaring that the U.S. regarded the western hemisphere as closed to further European colonization. As a result, Adams obtained a pledge from Russia to remain north of lat 54°40‘. The British, however, refused to vacate the Columbia River area.

President.

In 1824 Adams was involved in a bitter presidential contest in which none of the four candidates obtained a majority in the electoral college. Adams, with 84 votes (all from New England), ran behind Andrew Jackson (99) but ahead of William H. Crawford (41) and Henry Clay (37). Victory went to Adams in the House of Representatives, when Clay supported him. Adams’s choice of Clay as secretary of state led to a charge (probably unfounded) of a "corrupt bargain"—in effect, that Clay had purchased the office with his votes.

Adams’s presidency was marred by the incessant hostility of the combined Jackson and Crawford supporters in Congress, which prevented Adams from executing his envisaged nationalist program. His proposals for the creation of a department of the interior were rebuffed. Only after acrimonious debate did he obtain the appointment of delegates to a congress of the American nations in Panama (1826). Committed to the idea of a protective tariff, Adams in 1828 was maneuvered into signing the grossly unfair Tariff of Abominations, thereby alienating the South, as his enemies hoped he would. He steadfastly refused to use the federal patronage to strengthen his party support, allowing his postmaster general to appoint Jackson backers. In the election of 1828, pilloried as an aristocrat favoring special interests, Adams was overwhelmingly defeated by Jackson (178 to 83 electoral votes).

Later Congressional Service.

Two years after the end of his presidency, Adams returned to politics, entering the House of Representatives. Now nominally a Whig, he still followed an independent course. For ten years he chaired the Committee on Manufacturers, which drafted tariff bills. He lauded Jackson’s firm resistance to southern attempts to nullify the tariff of 1832, but condemned the compromise tariff of 1833 (not drafted by his committee) as being too great a concession to the nullificationists. After 1835 he was identified with the antislavery forces, although not with the abolitionists. Every year from 1836 to 1844 he led the fight to lift the gag rule that had ordered the tabling of all resolutions concerning slavery. He triumphed in 1844, when it was rescinded.

A vigorous speaker, Adams earned the sobriquet Old Man Eloquent. Throughout his lifetime he kept a voluminous diary, later edited by his son, Charles Francis Adams. On Feb. 21, 1848, he suffered a stroke on the floor of the House, and he died two days later without regaining consciousness