|

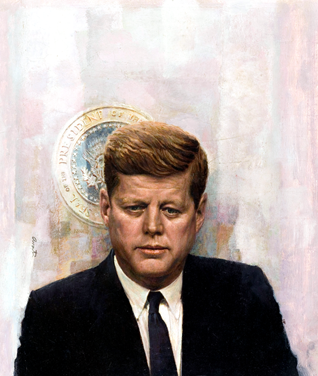

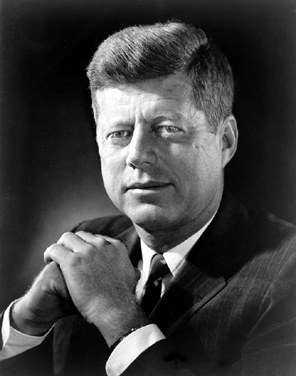

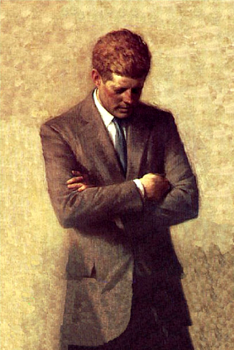

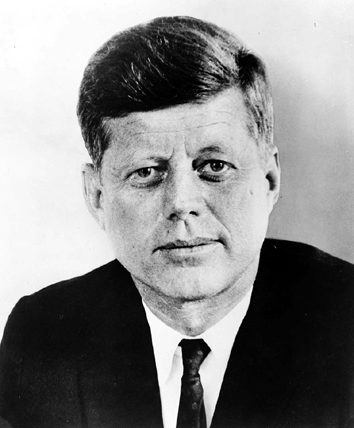

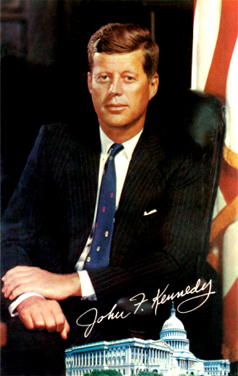

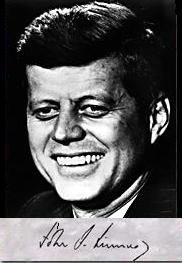

JOHN F. KENNEDY |

|

THE 35TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1961-1963)

KENNEDY, John Fitzgerald (JFK) "Jack"

(1917–63), 35th president of the U.S. (1961–63).Kennedy was born in Brookline, Mass., on May 29, 1917, the second son of financier Joseph P. Kennedy, who served as ambassador to Great Britain during the administration of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He graduated from Harvard University in 1940, winning notice with the publication of Why England Slept, an expansion of his senior thesis on Britain’s lack of preparedness for World War II. His own part in the war was distinguished by bravery. In August 1943, as commander of the U.S. Navy torpedo boat PT-109, he rescued several crewmen after the boat was rammed by a Japanese destroyer off the Solomon Islands.

Early Political Success.

Returning home to Boston with a citation for valor, the rich and ambitious young veteran joined the Democratic party and successfully ran for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1946. Massachusetts voters elected him to the U.S. Senate in 1952. In 1953 he married Jacqueline Bouvier; they were the parents of two children who survived infancy, Caroline Bouvier (1957– ) and John F., Jr. (1960–99). During recuperation from spinal surgery, Kennedy completed Profiles in Courage (1956), biographical sketches of political heroes, for which he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1957.

After an unsuccessful attempt to win the vice-presidential nomination on the ticket of Adlai E. Stevenson in 1956, Kennedy began to plan for the presidential election of 1960. He assumed the leadership of the Democratic party’s liberal wing and gathered around him a group of talented young political aides, including his brother and campaign manager, Robert F. Kennedy. He won the nomination on the first ballot and campaigned with Senator Lyndon B. Johnson of Texas as his running mate against Vice-President Richard M. Nixon, the Republican nominee. The issues of defense and economic stagnation were raised in four televised debates in which Kennedy’s poised and vigorous performance lent credence to his call for new leadership. Kennedy won the election by a narrow margin of 113,000 votes out of 68,800,000 cast, but had to accept reduced Democratic majorities in Congress. He was the youngest president ever elected and the first Roman Catholic.

The New Frontier.

President Kennedy’s inaugural address set a tone of youthful idealism that raised the nation’s hopes. "Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country," he exhorted. An early executive order of the New Frontier, as the administration called itself, established a Peace Corps of Americans volunteering for service abroad.

In 1961, his first year in office, Kennedy was battered by a series of adverse international developments. Inheriting from the previous administration a secret plan to overthrow the Cuban regime of Premier Fidel Castro, Kennedy approved an invasion of Cuba in April by refugees operating with the help of U.S. agencies. The abrupt failure of the invasion at the Bay of Pigs resulted in personal embarrassment for the president. Later in the spring Kennedy pondered sending U.S. troops into Laos, which was being threatened by Communist insurgents. He flew to Vienna in June to meet with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev. The two leaders agreed on a neutralized Laos, but Kennedy was chilled by Khrushchev’s grim warning that West Berlin was "a bone in my throat." When the wall between the eastern and western sectors of Berlin was erected in August, Kennedy responded by sending 1500 U.S. troops over the land route to Berlin to reaffirm access rights there. Cold War tensions were further aggravated when the Soviet Union sent the first man into space in April and resumed atmospheric nuclear tests in September.

The Cuban Missile Crisis.

In the fall of 1962 rumors began to mount that nuclear-armed Soviet missiles were being set up in Cuba. In October, U.S. aerial reconnaissance confirmed that middle-range missiles were indeed being installed. After a week of secret consultation with his advisers, on October 22 the president announced his intention of placing a naval blockade around Cuba to prevent the arrival of more missiles. He demanded that the Soviet Union dismantle and remove the missiles and bombers that had been detected. Communication between Khrushchev and Kennedy was opened through diplomatic channels. On October 28 Khrushchev acceded to the U.S. demands; Kennedy halted the blockade and gave assurances that the U.S. would not invade Cuba. The Soviet retreat was considered a personal and political triumph for the president.

Kennedy’s prospects in foreign affairs further improved in 1963, his final year. During a successful European tour he was warmly received in West Berlin, where he pledged continued support for West Germany. In June he delivered an innovative foreign policy speech calling for an end to the cold war. The two superpowers agreed to establish a "hot line" between Moscow and Washington, D.C., to facilitate communication in time of crisis. In July an agreement was reached with the Soviet Union and Great Britain on a nuclear test-ban treaty. The Alliance for Progress, a program of aid for Latin America, proved popular. These developments were clouded, however, by the worsening situation in South Vietnam, where Kennedy had committed 17,000 U.S. military advisers on behalf of an unstable regime beset by corruption and a growing Communist insurgency.

Domestic Affairs.

Kennedy’s wit and charm earned him considerable popularity at home and abroad, but he did not fare well with Congress. "Every president must endure a gap between what he would like and what is possible," he remarked ruefully in 1963, after his major proposals for economic stimulus, tax reform, aid to education, and broadened welfare had bogged down in congressional committees. He had better luck with executive actions—arguing major steel companies into rescinding price increases in April 1962 and stimulating the race to send an astronaut to the moon. Kennedy responded energetically against efforts to thwart school integration in the South. In September 1962 he appealed for compliance with the law when U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black ordered the University of Mississippi to accept James Meredith (1933– ), a black student. The president ordered 3000 federal troops to the campus to quell the ensuing riots. In 1963 Kennedy used the threat of federal force to help win partial desegregation of public accommodations in Birmingham, Ala., and of classrooms in Alabama public schools. To strengthen civil rights Kennedy sent to Congress a special message asking for legislation to desegregate public facilities and give the Justice Department authority to bring school integration suits. Most of his proposals were ultimately enacted in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Assassination Attempt.

December 11, 1960: While vacationing in Palm Beach, Florida, President-elect John F. Kennedy was threatened by Richard Paul Pavlick, a 73-year-old former postal worker. Pavlick intended to crash his dynamite-laden 1950 Buick into Kennedy's vehicle, but he changed his mind after seeing Kennedy's wife and daughter bid him goodbye. Pavlick was arrested three days later by the Secret Service after being stopped for a driving violation; police found the dynamite in his car. Pavlick spent the next six years in both federal prison and mental institutions before being released in December 1966.

Assassination.

In the fall of 1963 Kennedy began to plan his strategy for reelection. He flew across the country extolling the improvements in U.S.-Soviet relations, receiving generally favorable public responses.

President Kennedy was assassinated, while riding in an open limousine, with his wife Jacqueline, in a presidential motorcade through Dealey Plaza, in Dallas, Texas, at 12:30 pm Central Standard Time on Friday, November 22, 1963, while on a political trip to Texas to smooth over frictions in the Democratic Party between liberals Ralph Yarborough and Don Yarborough (no relation) and conservative John Connally. He was shot once in the throat, once in the upper back, with the fatal shot hitting him in the head. He was taken to Parkland Memorial Hospital for emergency medical treatment, but pronounced dead at 1:00 pm (CST). Although he was not formally declared dead until a half-hour after the shooting, he effectively died instantly. Only 46, President Kennedy died younger than any U.S. president to date.

Lee Harvey Oswald (1939–63), a former U.S. Marine, and an employee of the Texas School Book Depository from which the shots were suspected to have been fired, was captured hours after the assassination, at the Texas Theater. Oswald was arrested on charges for the murder of a local police officer, but was never subsequently charged with the assassination of Kennedy. He denied shooting anyone, claiming he was a patsy.

Two days later, at 11:21 a.m. Sunday, November 24, 1963, while he was handcuffed to Detective Jim Leavelle and as he was about to be taken to the Dallas County Jail, Oswald was shot and fatally wounded in the basement of Dallas Police Headquarters by, Dallas nightclub owner, Jack Ruby (1911–67) before he could be indicted or tried. Ruby, who said that he had been distraught over the Kennedy assassination, was then arrested. The shooting by Ruby was televised, as Oswald's transfer was being covered by the media. Oswald died instantly and was declared dead at Parkland Memorial Hospital just 10 feet from where the President was declared dead.

Jack Ruby was convicted for the murder of Oswald. He successfully appealed his conviction and death sentence but became ill and died of cancer on January 3, 1967, while the date for his new trial was being set.

President Johnson created the Warren Commission of 1963–1964—chaired by Chief Justice Earl Warren—to investigate the assassination, which concluded in September 1964 that Oswald was the lone assassin. The results of this investigation are disputed by many, and conspiracy theories persist. The assassination proved to be an important moment in U.S. history because of its impact on the nation and the ensuing political repercussions. A 2004 Fox News poll found that 66% of Americans thought there had been a conspiracy to kill President Kennedy, while 74% thought there had been a cover-up.

Funeral.

A Requiem Mass was held for Kennedy at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle on November 25, 1963. Afterwards, John F. Kennedy's body was buried in a small plot, (20 by 30 ft.), in Arlington National Cemetery. Over a period of 3 years, (1964–66), an estimated 16 million people had visited his grave. On March 14, 1967, Kennedy's body was moved to a permanent burial plot and memorial at the Cemetery. The funeral was officiated by Father John J. Cavanaugh. It was from this memorial that the graves of both Robert and Ted were modeled.

The honor guard at John Kennedy's graveside was the 37th Cadet Class of the Irish Army. Kennedy was greatly impressed by the Irish Cadets on his last official visit to Ireland, so much so that Jackie Kennedy requested the Irish Army to be the honor guard at the funeral.

Kennedy's wife, Jacqueline and their two deceased minor children were buried with him later. His brother, Senator Robert Kennedy, was buried nearby in June 1968. In August 2009, his brother, Senator Edward M. Kennedy, was also buried near his two brothers. John F. Kennedy's grave is lit with an "Eternal Flame". Kennedy and William Howard Taft are the only two U.S. Presidents buried at Arlington. According to the JFK Library, I Have a Rendezvous with Death, by Alan Seeger "was one of John F. Kennedy's favorite poems and he often asked his wife to recite it."

The state funeral of President Kennedy was watched on television by millions around the world.

Jacqueline Lee "Jackie" Bouvier Kennedy Onassis Died May 19, 1994 (aged 64), in Manhattan, New York City