|

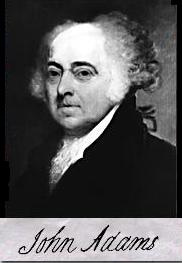

JOHN ADAMS |

|

THE 2ND PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1797-1801)

ADAMS, John (1735Ė1826), second president (1797Ė1801) and first vice-president (1789Ė1797) of the U.S., and leader in the movement for independence. His presidency was marked by rivalry with fellow-Federalist Alexander Hamilton, controversy over government measures taken to curb political opposition, and a crisis in U.S. relations with France.

Adams was born on Oct. 30, 1735, in Braintree (now Quincy), Mass., a town in which Adamses had lived since 1638. His father had married into a wealthy Boston family, the Boylstons, and was thus able to send his son to Harvard College, from which young Adams graduated in 1755. He then selected law and soon found that in the courtroom his acquired erudition and intellectual precision overcame his natural timidity, and he became a powerful speaker and an adroit advocate. At the age of 29 Adams married Abigail Smith, a woman who was clearly his intellectual and psychological equal.

The Coming of the Revolution.

The controversy that preceded the American Revolution catapulted Adams into a position of political leadership. His Braintree Instructions (1765) was a powerful denunciation of the Stamp Act, and his oddly titled Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law (1765) was a prescient analysis of the emotional and ideological demands facing the colonists. Chosen as a lawyer for several British soldiers charged with the death of five colonists in the Boston Massacre (1770), Adams successfully defended his clients by justifying their use of force out of fear for their lives. In his essays Novanglus (1774Ė75), he defended colonial resistance and argued that the British Empire was in reality a league of nearly autonomous entities; thus, he anticipated 19th-century self-government of British overseas possessions.

In the First and Second Continental Congresses, Adams emerged as a powerful exponent of the historic rights of the English and the natural rights of humankind. Along with his cousin Samuel Adams, he initiated (1775) the effort to secure the appointment of George Washington as commander of the new Continental army. Adams served on the committee to draft the Declaration of Independence, but when Thomas Jefferson later claimed that Adams had given him a free hand in composing it, Adams responded indignantly that the document was "a theatrical show" in which "Jefferson ran away with the stage effect. . . and all the glory of it." Thus began a rivalry between the two men that continued for more than a decade.

More clearly perhaps than any other leading patriot of his day, Adams expressed the fear that he and his fellow revolutionaries might fail in summoning forth the virtue and objectivity required to avoid loss of nerve and internal factionalism. His Thoughts on Government (1776), in which he elaborated on these warnings, became a handbook on the writing of early state constitutions and particularly influenced the preparation of those documents in Virginia, North Carolina, and Massachusetts.

Diplomatic Service and Vice-Presidency.

In 1778 Congress sent Adams and John Jay to join Benjamin Franklin as diplomatic representatives in Europe. Franklin remained the American envoy to France; Adams went to the Dutch Republic and had the responsibility for opening negotiations with Britain; Jay traveled to Spain. In 1782 and 1783, the three men together negotiated the Treaty of Paris, ending the 8-year war with Great Britain.

In 1785 Adams was appointed diplomatic envoy to Great Britain, a position he held until 1788. His duties in England caused him to miss the Constitutional Convention and the ratifying debates. He had played a crucial role earlier, however, in drafting the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780. While in London he wrote the three-volume Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. This work rebutted a French critic of American politics and reiterated Adamsís belief that only formal restraints on the exercise of power and on the impulses of the populace could militate against human evil and societal weaknesses.

Because he ran second to Washington in electoral-college balloting in both 1788 and 1792, Adams became the nationís first vice-president. In that capacity, he limited himself to presiding over the Senate.

The Presidency.

In 1796 Adams was chosen to succeed Washington as president, winning over Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Pinckney. The threat of war with France, along with the resulting passionate debate over foreign policy and the limits of dissent, dominated the politics of his administration. The war scare was sparked by American indignation over French attempts to extort money from U.S. representatives in the so-called XYZ Affair. A conflict arose over the measures to be taken in preparation for possible hostilities. Adams favored strengthening the navy and building coastal fortifications, but an opposing group led by former secretary of the treasury Alexander Hamilton persuaded Congress to create a large standing army, with Hamilton himself as inspector general. Because the possibility of a French invasion of the U.S. was remote, the clear implication of this policy was the creation of an army the size and strength of which could intimidate opposition of the Republican voters.

Alien and Sedition Acts.

The Hamilton Federalists added substance to those fears by pushing through Congress laws restricting the rights and privileges of aliens (presumed to be potential Republican voters or, worse yet, French radicals) and punishing as sedition the printing of false attacks on the dignity or integrity of high government officials. Adams found enough merit in these bills to sign them, and he acquiesced in 14 prosecutions under the Sedition Act. The Alien Acts, however, he refused to enforce.

One of Adamsís most fateful decisions was to retain the cabinet he had inherited from Washington, several members of which were personally loyal to Hamilton. Together with Hamiltonís supporters in Congress, they engineered the creation of the new army, which Hamilton in actuality controlled.

Agreement with France.

Adams did, however, demonstrate the power of the presidency to confront challenges to executive leadership. In February 1799, he appointed new peace commissioners to go to France and reopen negotiations. Adamsís timing and judgment were acute: The French foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord, had sent a diplomatic signal that he wanted peace with the U.S. When Secretary of State Timothy Pickering, a Hamilton follower, tried to sabotage the peace mission, Adams fired him; shortly thereafter the two nations came to terms.

The peace initiative enabled Adams to dismantle the new army, much to Hamiltonís embarrassment. Adamsís foreign policy, however, split the Federalist party on the eve of the 1800 election and contributed significantly to the election of Thomas Jefferson as well as to Republican victories in both houses of Congress.

Retirement.

Adams lived for a quarter century after he left the presidency, during which time he wrote extensively. His guiding principles were embodied in a Whig philosophy to which he clung stubbornly. Ill-suited to adapt to the transition to 19th-century romantic culture, he was nevertheless a magnificent exponent of the pessimistic view of human society. He died in Quincy, Mass., on July 4, 1826.