|

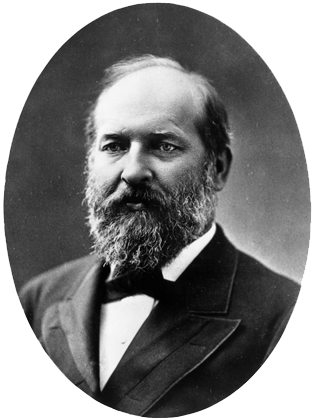

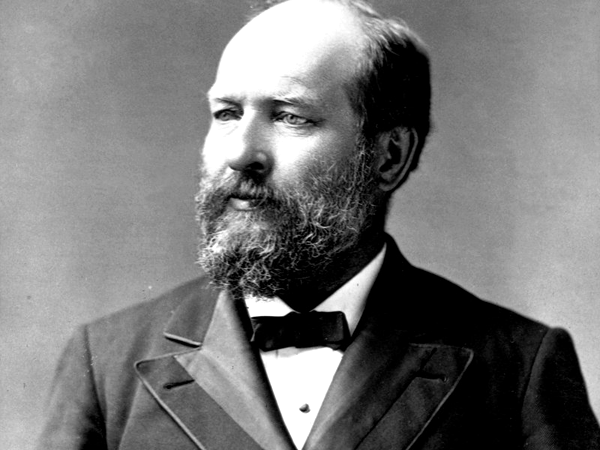

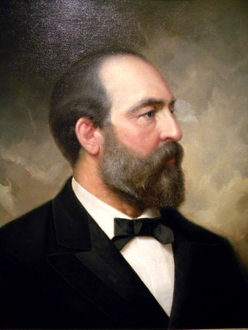

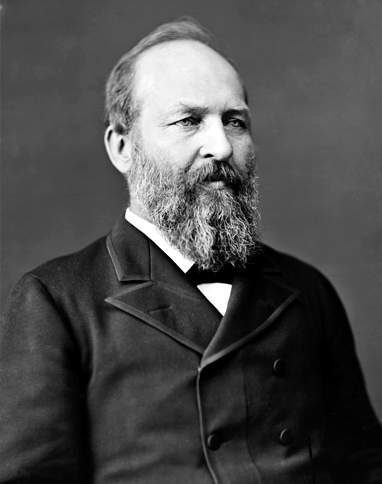

JAMES GARFIELD |

|

THE 20TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1881)

GARFIELD, James Abram

(1831–81), 20th president of the U.S. (1881), who during his brief term asserted presidential prerogatives against the demands of congressional leaders.Garfield was born in a log cabin in Cuyahoga Co., Ohio, on Nov. 19, 1831. Raised in poverty by his widowed mother, and doing every kind of rough frontier work, he managed to secure a college education and to develop oratorical skills that quickly led him from lay preaching for the Disciples of Christ into politics. He was married in 1858 to Lucretia Rudolph (1832–1918) and was elected to the Ohio legislature the year after. When the American Civil War came, he raised a regiment and soon displayed considerable talent as an administrator and military leader.

Military and Congressional Career.

In January 1862, when Union victories were rare, Garfield’s troops defeated a Confederate army at Middle Creek, making Garfield a hero and resulting in his promotion to brigadier general of volunteers. Military glory and his antislavery record won him a seat in Congress in 1863. Garfield went to Washington with brilliant prospects marred only by his lack of wealth and his tendency, already manifest, to participate in rather dubious business undertakings that traded on his military fame and political position.

Garfield was a talented parliamentarian, a hard worker, and a skilled negotiator in Congress. His work on the House Appropriations Committee made a real contribution to improving the management of the U.S. government. When James G. Blaine advanced to the Senate in 1876, Garfield succeeded him as leader of the House Republicans; as such he was a brilliant debater and a consistent but sensible partisan. In 1880, when Republican factions deadlocked at the national convention, he was an obvious compromise choice for the party’s presidential nomination.

Garfield as President.

Factional battling within the Republican party marked the 1880 campaign, which was further marred by the airing of two financial scandals that loosely implicated Garfield—one involving the paving of Washington, D.C., streets and the other the building of the transcontinental railroads. Then, as throughout his career, Garfield deflected his accusers, but he could never fully deter them. With the Republican factions finally cooperating and a New Yorker, Chester Arthur, as his vice-presidential candidate, Garfield became president with a scant margin of 10,000 votes.

Garfield’s brief administration was consumed largely by a war with Sen. Roscoe Conkling of New York over patronage. Garfield had appointed James Blaine, Conkling’s greatest enemy, as secretary of state and then named a Blaine supporter to the politically critical position of collector of the Port of New York. Conkling, upholding the tradition of "senatorial courtesy," questioned the president’s right to make New York appointments over the objection of the state’s senator. After a bitter battle in which it became clear that the Senate would confirm Garfield’s nominee, Conkling and Thomas Platt (1833–1910)—New York’s junior senator—resigned their seats, seeking vindication through reelection by the New York legislature. Conkling’s plan backfired: The legislature sent two new senators to Washington, ending Conkling’s career and giving Garfield a triumph.

On July 2, 1881, Charles Jules Guiteau (c. 1840–82), a disappointed office seeker, shot Garfield; he lingered on until September 19, when he finally succumbed. Garfield’s death at the hands of a frustrated office seeker created a powerful impetus for civil reform. His administration, which initiated prosecutions for mail-contract frauds in the previous administration, in addition to fighting the battles with Conkling, had importance principally in asserting the power of the president against Congress and in attacking corruption in government.