|

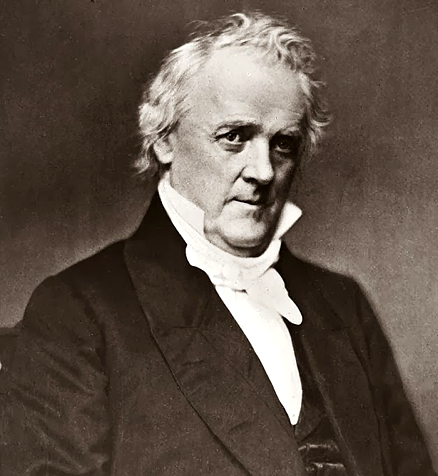

JAMES BUCHANAN |

|

THE 15TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1853-1857)

BUCHANAN, James

(1791–1868), 15th president of the U.S. (1857–61), who tried unsuccessfully to stave off the crisis that led to the American Civil War.Buchanan was born on April 23, 1791, near Mercersburg, Pa., the son of prosperous Scotch-Irish Presbyterians. After graduating from Dickinson College, he studied law in Lancaster, Pa., where in 1812 he was admitted to the bar and soon established a flourishing practice. An able and resourceful advocate, he moved freely in society and enjoyed the company of women, but after the early death of a fiancée who had broken with him, he remained a bachelor.

Early Career.

A Federalist in politics, Buchanan was twice elected to the Pennsylvania General Assembly (1814, 1815), and in 1821 he entered the U.S. Congress. Eventually joining the coalition that in 1828 elected Andrew Jackson president, he became a loyal Democrat, although he generally remained a moderate on such partisan issues as tariff and bank policies.

After briefly serving (1832–33) as minister to Russia, Buchanan was elected U.S. senator from Pennsylvania. A conciliator rather than an innovator, he sought to harmonize the various factions of the Democratic party. In 1845 he became President James K. Polk’s secretary of state, a position in which he again counseled moderation, particularly in connection with annexations in Mexico and Oregon. In 1852 President Franklin Pierce appointed him minister to Great Britain, a mission that kept him away from the country during the Kansas-Nebraska Act controversy. He incurred criticism by joining the U.S. ambassadors to Spain and France in signing the Ostend Manifesto (1854), which declared the U.S.’s right to take Cuba by force should efforts to purchase the slaveholding island fail. Nevertheless, two years later he won his party’s nomination for the presidency.

The Presidency.

In 1856 Buchanan defeated John C. Frémont, a Republican, and the former president Millard Fillmore in their bid for the presidency. Acceptable both to Northern Democrats and Southern moderates, he ran on a platform of popular sovereignty (the right of settlers in a territory to decide whether or not to sanction slavery). Within two days of his inauguration, however, in the Dred Scott decision, of which he had prior knowledge, the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Constitution protected slavery in all territories. The president’s difficulties multiplied with the depression caused by the Panic of 1857 and with his support for the admission of Kansas to the Union as a slave state. This aroused opposition in Buchanan’s own party.

Seeking to steer a middle course between the widely divergent philosophies of the South and North, Buchanan was unable in 1860 to prevent the breakup of his party or afterward to reunite the factions, one of which supported Vice-President John C. Breckinridge and the other Sen. Stephen A. Douglas. In the secession crisis following the victory of Republican Abraham Lincoln, Buchanan sought to gain time to allow passions to cool. Declaring that secession was illegal but that he had no power to prevent it, he attempted to preserve the peace by not provoking secessionists. Stiffening somewhat after the reorganization of his cabinet, he refused Southern demands that federal troops be ordered to abandon Fort Sumter in the harbor of Charleston, S.C. His efforts to supply the fort failed, however, as did his plans for a constitutional convention. He left office disappointed and discredited.

Well-intentioned and dignified, but a weak executive, Buchanan had the misfortune of holding office during an extremely difficult period. He died at his estate, Wheatland, in Lancaster, on June 1, 1868.