|

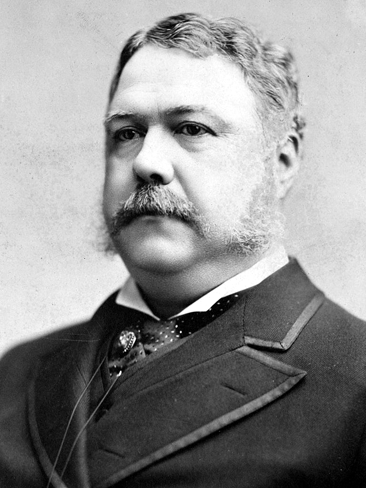

CHESTER A. ARTHUR |

|

THE 21ST PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1881-1885)

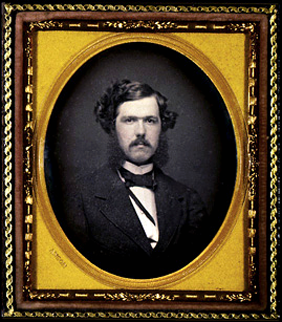

ARTHUR, Chester Alan

(1830–86), 21st president of the U.S. (1881–85), who rose above a background of political corruption to head a reform-oriented administration that enacted the first comprehensive U.S. civil service legislation.

Early Career.

Arthur was born in Fairfield, Vt., on Oct. 5, 1830, the son of a poor country preacher. He graduated from Union College in Schenectady, N.Y., taught school, and then studied law and opened a practice in New York City before the American Civil War. A moderate abolitionist, he defended several runaway slaves and was an early activist in the New York Republican party. With the coming of the war, Arthur became New York’s quartermaster-general in charge of supplying the state’s volunteers with equipment. He performed this huge administrative task with efficiency and scrupulous honesty, earning an important place for himself in the state Republican organization, which was dominated by the so-called Stalwart faction. In 1871 he became collector of the Port of New York. Arthur administered the collection of customs with his usual care and honesty while directing his approximately 1000 employees in doing political work for the state Republican party and its leader, Senator Roscoe Conkling.

Arthur’s position became difficult when the federal government investigated the Custom House and issued an order banning civil servants from managing political affairs. When Arthur ignored the order at Conkling’s request, President Rutherford B. Hayes had Arthur and his naval officer, Alonzo B. Cornell (1832–1904), removed from office. But Arthur retained the support of the New York party, and when James A. Garfield was nominated for president in 1880, his managers chose Arthur as their vice-presidential candidate to placate the Conkling faction. After Garfield’s election, Arthur became his ally in a dispute with Conkling. Garfield died, the victim of an assassin, on Sept. 19, 1881, and Arthur became president.

The Presidency.

Arthur as president put his Stalwart friends behind him, committing his administration to moderate reforms and maintaining the dignity of his office. He renovated the White House with his own ample funds (he had invested his money wisely over the years) and entertained in an opulent but tasteful style. He gradually changed Garfield’s cabinet, but his own administration never took on any distinctive tone. He supported the civil service reform bill that became law in 1883, but never became fully identified with it in the public mind. Similarly, he worked toward the first downward revision of the tariff since the Civil War, but the bill, achieved in 1883, scarcely made a dent in the structure of protection. He vigorously prosecuted frauds uncovered during the Garfield administration, but the government failed to gain convictions. Arthur vetoed a Chinese exclusion bill that clearly violated a treaty with China and also vetoed a wasteful rivers and harbors bill, which Congress promptly passed over his veto.

Arthur succeeded in gaining respect as president, but he generated little political enthusiasm. And, unknown to his contemporaries, he was dying of kidney failure. He effectively hid his illness from the public and even made desultory attempts at the Republican nomination for 1884, but this was probably only because of intense pride. Leaving office in 1885, honored but unlamented, he died of nephritis on Nov. 18, 1886.