|

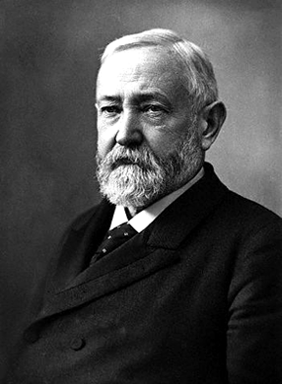

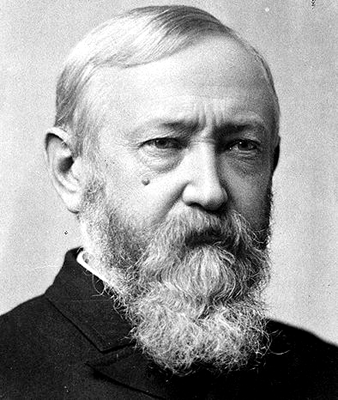

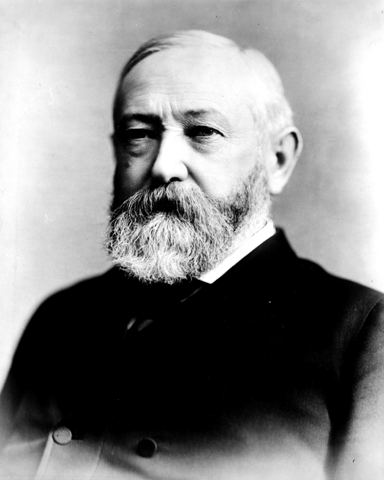

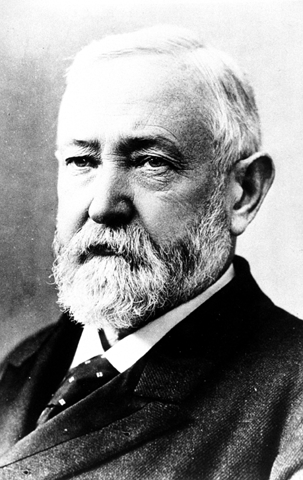

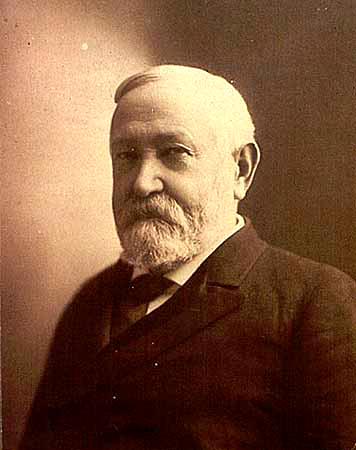

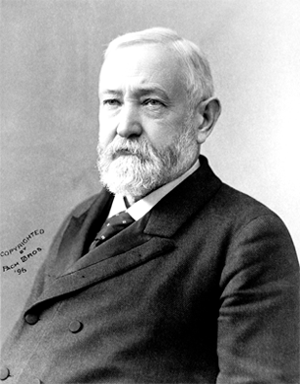

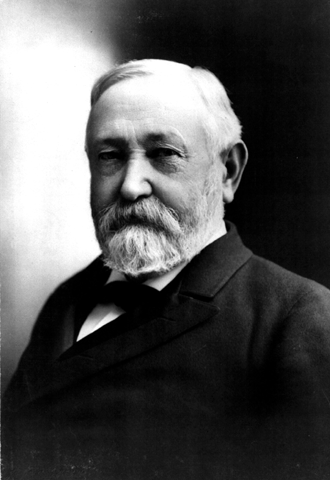

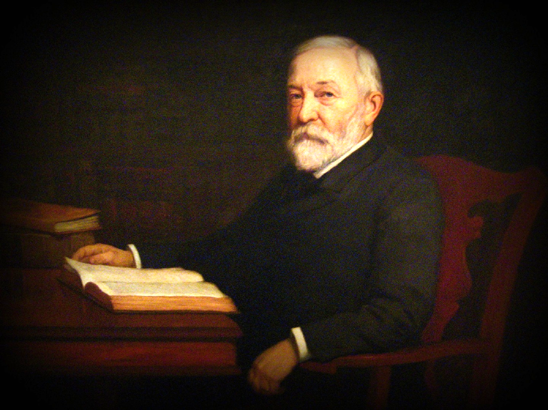

BENJAMIN HARRISON |

|

THE 23RD PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1889-1893)

HARRISON, Benjamin

(1833–1901), 23d president of the U.S. (1889–93), who directed a reformulation of the Monroe Doctrine that was to end American isolationism and set the stage for future territorial and trade expansion.Harrison was born on Aug. 20, 1833, at North Bend, Ohio. The grandson of President William Henry Harrison, and the great-grandson of Benjamin Harrison V, a Virginia governor and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Harrison was seven years old when his grandfather was elected President, but he did not attend the inauguration. He grew up on his father’s farm on the banks of the Ohio River. After graduating from Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, he took a law clerkship in Indianapolis. Before completing his law studies, Harrison returned to Oxford and married his college sweetheart, Caroline Lavinia Scott (October 1, 1832 – October 25, 1892). She was the daughter of the college president, John Witherspoon Scott, a Presbyterian minister. On October 20, 1853, they married with Caroline's father performing the ceremony. The Harrisons had two children, Russell Benjamin Harrison (August 12, 1854 – December 13, 1936), and Mary "Mamie" Scott Harrison (April 3, 1858 – October 28, 1930). He soon became involved in the newly formed Republican party, serving as secretary to the state convention and as a popular campaign speaker.

During the American Civil War, Harrison helped raise Indiana’s 70th Infantry and became its commander. He was promoted to brigadier general after serving with distinction in the Atlanta campaign. When peace came, he returned to his law practice in Indianapolis and resumed activities in the Republican party. Defeated in a bid for the governorship of Indiana in 1876, he served in the U.S. Senate from 1881 to 1887.

Harrison was known as the Centennial President because his inauguration celebrated the centenary of the first inauguration of George Washington in 1789.

Harrison as President.

In 1888 party factionalism prevented the nomination of the leading presidential contender, James G. Blaine, and Harrison, a dark horse, won the Republican party’s nomination for the presidency.

Harrison defeated the incumbent, Grover Cleveland, on a platform of protectionism. As president, however, Harrison was never a charismatic leader, nor was he able to negotiate alliances with Congress to obtain support for his policies. His isolation from Congress promoted further charges of coldness ("cold as ice" had been a description of his gubernatorial candidacy) and lost him the support of many party members. He continued the civil service reforms of his predecessors, but at a moderate pace, alienating both those Republicans who were looking for spoils and those urging more rapid reform. Moreover, although he had campaigned on a platform of liberalizing veterans’ pensions, he was forced to remove his own commissioner of pensions for lavishly and scandalously distributing awards.

Harrison experienced difficulty in maintaining a stable national economy. The Bland-Allison Act of 1878 required the treasury to buy $2 million of silver for coinage each month. As the market value of silver fell, the president sought to limit coinage. Advocates of free coinage forced a compromise bill, the Sherman Silver Purchase Act (1890), which required the government to buy more silver but limited coinage. The increased purchase drained gold from the reserves, and Harrison twice had to avert panic by releasing more currency.

Harrison had campaigned on a platform of increasing protectionist tariffs. Although the public supported increased tariffs at the time of the election, the effect of the McKinley Act (1890) was to contribute to inflationary prices for necessities, and protectionist tariffs ultimately became unpopular.

He increased the size of the merchant marine to facilitate expanded trade and of the navy to protect commercial interests abroad. The first Pan-American Conference, held during his administration, created new commercial and diplomatic ties between the U.S. and independent republics in Latin America.

When Harrison took office, no new states had been admitted in more than a decade, owing to Congressional Democrats' reluctance to admit states that they believed would send Republican members. Early in Harrison's term, however, the lame duck Congress passed bills that admitted four states to the union: North Dakota and South Dakota on November 2, 1889, Montana on November 8, and Washington on November 11. The following year two more states held constitutional conventions and were admitted: Idaho on July 3 and Wyoming on July 10, 1890. The initial Congressional delegations from all six states were solidly Republican. More states were admitted under Harrison's presidency than any other since George Washington's.

Re-election campaign in 1892.

The Democrats renominated former President Cleveland, making the 1892 election a rematch of the one four years earlier. The tariff revisions of the past four years had made imported goods so expensive that now many voters shifted to the reform position. Many westerners, traditionally Republican voters, defected to the new Populist Party candidate, James Weaver, who promised free silver, generous veterans' pensions, and an eight-hour work day. The effects of the suppression of the Homestead Strike rebounded against the Republicans as well, although the federal government did not take action.

Two weeks before the election, on October 25, Harrison's wife Caroline died after a long battle with tuberculosis. Harrison did not campaign on his own behalf during his re-election bid and remained with his wife. Their daughter Mary Harrison McKee served as the First Lady after her mother's death.

Cleveland ultimately won the election with 277 electoral votes to Harrison's 145. Cleveland also won in the popular vote: 5,556,918 to 5,176,108.

Post-presidency, Later Career, and death.

After he left office, Harrison visited the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in June 1893, where the nation's first commemorative postage was introduced, an initiative of his Postmaster General, John Wanamaker. After the Expo, Harrison returned to his home in Indianapolis.

For a few months in 1894, Harrison lived in San Francisco, California, where he gave law lectures at Stanford University. A loyal Republican, Harrison continued to serve as his party’s spokesman. In 1896 some of Harrison's friends in the Republican party tried to convince him to seek the presidency again, but he declined. In support of the candidate William McKinley, he traveled around the nation making appearances and speeches in his behalf.

Among the activities he became involved in, from July 1895 to March 1901, Harrison served on the Board of Trustees of Purdue University. Harrison Hall, a campus dormitory, was named in his honor.

In 1896, Harrison at age 62 remarried, to Mary Scott Lord Dimmick, the niece and former secretary of his deceased wife. A widow, she was 37, a full 25 years his junior. Harrison's two children were adults, Russell, 41 years old at the time, and Mary (Mamie) McKee, 38, disapproved of the marriage and did not attend the wedding. Benjamin and Mary had one child together, Elizabeth (February 21, 1897 – December 26, 1955).

In 1889, Harrison was elected an honorary member of the Pennsylvania Society of the Cincinnati. Harrison was also a veteran companion of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States and an honorary companion of the Military Order of Foreign Wars. His wife served as the first President General of the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR) from 1890 to 1891.

He wrote a series of articles about the Federal government and the presidency, which were republished in 1897 as a book titled This Country of Ours, that was well received and widely read. In 1899 Harrison attended the First Peace Conference at The Hague.

In 1900, Harrison served as an attorney for the Republic of Venezuela in their boundary dispute with the United Kingdom. The two nations disputed the border between Venezuela and British Guiana (now Guyana). An international trial was agreed upon and the Venezuelan government hired Harrison to represent them in the case. Earning respect for his legal expertise, he filed an 800-page brief for them and traveled to Paris where he spent more than 25 hours arguing in court. Although he lost the case, his legal arguments won him international renown.

Harrison developed what was thought to be influenza or grippe in February 1901. He was treated with steam vapor inhalation and oxygen, but his condition worsened. He died a respected elder statesman, on Wednesday, March 13, 1901, at the age of 67, from pneumonia at his home, in Indianapolis, Indiana. Harrison is interred in Indianapolis's Crown Hill Cemetery, next to Caroline. After her death, Mary Dimmick Harrison was buried next to him.

Historical reputation and memorials.

Following the Panic of 1893, Harrison became more popular in retirement. His legacy among historians is scant, and "general accounts of his period inaccurately treat Harrison as a cipher".

More recently, "historians have recognized the importance of the Harrison administration—and Harrison himself—in the new foreign policy of the late nineteenth century. The administration faced challenges throughout the hemisphere, in the Pacific, and in relations with the European powers, involvements that would be taken for granted in the twentieth century."

Harrison's presidency belongs properly to the 19th century, but he "clearly pointed the way" to the modern presidency that would emerge under William McKinley. Harrison's reputation for integrity was largely intact after leaving office in 1893. The bi-partisan Sherman Anti-Trust Act signed into law by Harrison remains in effect over 120 years later and was the most important legislation passed by the Fifty-first Congress. Harrison's support for African American voting rights and education would be the last significant attempts to protect civil rights until the 1930s. Harrison's tenacity at foreign policy was emulated by politicians such as Theodore Roosevelt.

Harrison was memorialized on several postage stamps. The first was a 13-cent stamp issued on November 18, 1902. The engraved likeness of Harrison was modeled after a photo provided by Harrison's widow. In all Harrison has been honored on six U.S. Postage stamps, more than most other U.S. Presidents. Harrison also was featured on the five-dollar National Bank Notes from the third charter period, beginning in 1902. Harrison was also the last president to have a beard.

In 1908, the people of Indianapolis erected the Benjamin Harrison memorial statue, created by Charles Niehaus and Henry Bacon, in honor of Harrison's lifetime achievements as military leader, U.S. Senator, and President of the United States.

In 1942, a Liberty Ship, the SS Benjamin Harrison, was named in his honor. In 1951, Harrison's home was opened to the public as a library and museum. It had been used as a dormitory for a music school from 1937 to 1950. The house was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1964. In 2012, a dollar coin with his image, part of the Presidential $1 Coin Program, was issued.

Fort Benjamin Harrison, located in suburban Lawrence, Indiana, northeast of Indianapolis, was named in his honor. The base was closed and the site has been redeveloped to include residential neighborhoods and a golf course. Part of the property is within Fort Harrison State Park.