|

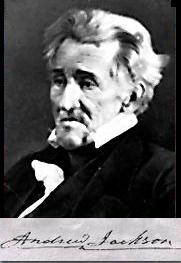

ANDREW JACKSON |

|

THE 7TH PRESIDENT OF

THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

(1829-1837)

JACKSON, Andrew

(1767–1845), seventh president of the U.S. (1829–37), the first president of humble origins. His election to the highest office in 1828 was long regarded as a great victory for the common people, and the political movement he led was known as Jacksonian Democracy.Early Career.

Born March 15, 1767, of a Scotch-Irish immigrant family in the Waxhaw settlement on the western frontier of South Carolina, Jackson was orphaned at the age of 14 and was brought up by an uncle who was a well-to-do slave owner. As a result, the young Jackson moved among wealthy men who monopolized prestige and political influence in the backcountry. He became a lawyer at age 20 and as a prosecuting attorney in Nashville, Tenn., showed no sympathy for debtors unable to meet their mortgage payments. Blessed with great courage and an iron-willed determination that inspired fear and respect among those who crossed his path, Jackson quickly became one of the leaders in the new state of Tennessee. His marriage to Rachel Donelson Robards (1767–1828), whose father had great prestige, abetted Jackson’s career and social standing. Jackson and his wife were unaware, however, at the time of their marriage that her divorce from her first husband had not yet been technically completed, and his political enemies thereafter referred to the couple as adulterers.

After helping to draft the Tennessee constitution in 1796, Jackson was elected the state’s first congressman, serving one year in the U.S. House of Representatives and then for a year in the U.S. Senate. In 1798 he was appointed judge of the superior court in Tennessee. Feared for his hair-trigger temper and his prowess as a duelist, in 1802 Jackson was elected major general of the Tennessee militia. He was by this time a slave owner, businessman, and land speculator. Although his commercial fortunes fluctuated, he was generally a successful property owner. As an ambitious man, however, he longed to play a greater part in the nation’s affairs; the outbreak of the War of 1812 provided this opportunity.

Military Successes.

In the early part of the war Jackson’s feats in crushing the Creek Indians won him national acclaim. The Creeks were British allies, who had threatened U.S. southwestern borders. Jackson’s decisive victory at Horseshoe Bend, Ala., in March 1814, destroyed the Creeks; the harsh peace treaty he imposed deprived them of more than 8 million ha (20 million acres) of land—an area larger than that of most of the states in the Union. Old Hickory, as Jackson was now known because of his toughness, had given the nation a taste of military glory. On Jan. 8, 1815, Jackson’s motley army won an amazingly one-sided victory at New Orleans over a British army composed largely of veterans. Jackson became a national hero. Detractors scoffed that his victory had come after the peace treaty ending the war had been signed in Europe. Had the British taken New Orleans, however, they undoubtedly would have held on to it, treaty or no treaty. Good Democrats to this day celebrate January 8.

The Road to the Presidency.

In the years immediately following, Jackson maintained his prominence but not without creating a furor—as his actions often did. Early in 1818, without clear authorization, he violated Spanish-owned territory by chasing the hostile Seminole Indians into Florida, where he then created another international incident by putting two British subjects to death. Although this behavior disturbed the administration of President James Monroe, it was enthusiastically endorsed by the nationalistic majority of Americans. In 1821 he was appointed governor of Florida (ceded by Spain to the U.S. in 1819), and his high-handed actions in that office created new diplomatic storms. Nothing, however, could detract from his glowing reputation. Influential Tennessee friends made plans early in the 1820s to have Jackson run for the presidency in 1824.

Although Jackson at first professed a lack of interest, claiming he was not fit to hold the office, he quickly shed his reservations. He accepted a seat in the Senate in 1823, the better to promote his nomination, and the following year he became one of five presidential candidates. Jackson received a plurality of electoral votes, but in the absence of a majority, the names of the three leading vote-getters were placed before the House in accordance with the provisions of the U.S. Constitution. When the House chose John Quincy Adams president, and Adams in turn appointed Henry Clay secretary of state, Jackson and his supporters were furious. They charged that Adams and Clay had devised a "corrupt bargain," in which the new president paid off Clay for having used his influence in the House to swing the vote against Jackson. Never letting up on this charge, the Jacksonians harassed the Adams administration incessantly and effectively. Profiting from the excellent organization of the new Democratic party and its masterful electoral tactics, Jackson won a smashing victory in 1828 after perhaps the most vicious presidential election campaign in U.S. history.

First Administration.

Brilliant propagandists, the Democrats had depicted Old Hickory as a man devoted to the common people. Many of Jackson’s supporters, however, did not know where he stood on the issues of the day, either because of his silence or his lack of clarity. He nevertheless proved to be a surprisingly effective as well as vastly popular president. In replacing longtime federal officeholders with appointees of his own party, Jackson claimed that he was substituting commoners for aristocrats. In vetoing a bill that called for federal assistance in the laying of a road in Clay’s home state of Kentucky, Jackson posed as defender of strict construction of the Constitution. In refusing to interfere when Georgia violated Indian rights on territories guaranteed by federal treaty, he appeared as the champion of states’ rights. In threatening to send federal troops into South Carolina if that state persisted in its attempts to nullify or ignore the tariff laws, Jackson appeared to be a strong supporter of national power. Finally, in perhaps the most significant act of his first administration, Jackson told the nation that his veto on July 10, 1832, of the bill to recharter the Second Bank of the United States was a blow against monopoly, aristocratic parasites, and foreign domination and a great victory for honest labor. Most historians think that the actual effect of Jackson’s banking policy was to destabilize the nation’s currency and help bankers friendly to Jackson.

During his first term Jackson frequently relied for advice on an informal group derided by his opponents as the "Kitchen Cabinet"—supposedly because they met in the White House kitchen. Martin Van Buren and John H. Eaton (1790–1856), who belonged to this group, were also members of the official cabinet.

Second Administration.

Jackson’s reelection in 1832 by a large majority indicated the popularity of his policies. Of course, not everyone agreed with them. Some of his supporters thought his financial policies a disaster. Nevertheless, they remained publicly uncritical and loyal to him, because they were convinced that to desert him, even when he was wrong, was political suicide.

In 1834 an opposition party, the Whigs, was formed in order to fight what they called "King Andrew" and his tyranny. They were incensed above all by Jackson’s decision to place federal moneys in the vaults of so-called pet banks, under the direction mainly of Democratic bankers, rather than with the more reliable Bank of the United States (the charter of which was to run out in 1836). In pushing through this policy, Jackson dismissed two secretaries of the treasury who would not go along with him and brushed aside the opposition of a congressional majority. Led by Henry Clay, the Senate, for the only time in its history, in 1834 voted to censure a president, charging Jackson with dictatorial and unconstitutional behavior. Jackson and his friends did not rest until they succeeded three years later in physically expunging from the record of the Senate the evidence of the censure. Nevertheless, when Jackson left office in 1837, he was beloved by the people; he withdrew to the Hermitage, his magnificent residence outside Nashville, where he died on June 8, 1845.

Evaluation.

Modern historians are skeptical of the Jackson legend. They note that Jackson and his party did not so much expand political democracy as they used and benefited from it. They observe that Jackson was a large slave owner and that his party was the enemy of free blacks and their rights. They point to Jackson’s willingness to deny antislavery pamphlets the use of the U.S. mails. They decry the cruelties, illegality, and hypocrisy of his Indian policy, which forcibly removed southern tribes from lands guaranteed them by federal treaties and U.S. Supreme Court decisions. They observe that for all of Jackson’s talk of helping working people, Democratic policies accomplished little. They are dismayed by Jackson’s addiction to violent confrontation in foreign policy, as in 1835, when he brought the country to the brink of war with France over that nation’s delay in paying its debt to the U.S.

Jacksonians called their political opponents aristocrats, themselves the party of the people. In fact, Jacksonian leaders were almost everywhere as atypically wealthy, as unrepresentative of the common people, as were the Whigs. Many Jacksonian civil-service appointees were notorious not for being commoners but for their inefficiency or their flagrant corruption.

Jackson did help revolutionize and strengthen the presidency. He vetoed more bills, for example, than had all his predecessors combined. Furthermore, in vetoing bills merely because he disliked them, he repudiated the tradition originated by George Washington that the veto was a hangover from monarchy, rarely to be exercised by presidents in a republic. Since Jackson’s time it has been commonplace for presidents to repeat the Jacksonian assertion that the president represents the will of the people better than does Congress. Jackson’s chief legacy to the nation was what political scientists call the strong presidency and a tradition whereby leaders and parties constantly proclaim their love of the people.